In 2023, 51 patients with no fixed address visited UHN’s emergency departments more than 3,300 times, often needing supports beyond medical care. An innovative program is helping meet the complex needs of these and other patients experiencing homelessness while supporting an emergency department team facing ever-increasing patient volumes: peer support workers.

Through the peer support workers program – launched at UHN in 2020, a partnership between UHN’s Gattuso Centre for Social Medicine and The Neighbourhood Group Community Services – people with lived experience of homelessness and substance use provide specialized care for patients facing these same challenges.

An integral part of the emergency department team, peer support workers talk one-on-one with patients to figure out how they can help, whether that’s grabbing them something to eat, calling shelters to find an available bed, or advocating for their care needs.

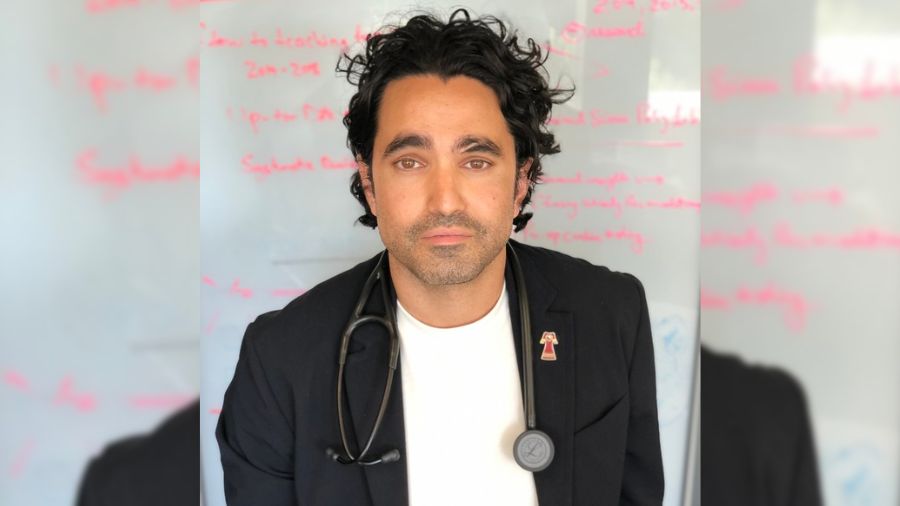

“Peers’ input helps us understand a patient’s history and realities, including recognizing vulnerabilities that often go unnoticed in the chaotic emergency department environment,” says Dr. Kathryn Chan, UHN emergency medicine and addictions physician, and Health Equity Co-Lead within the emergency department.

Building trust as the foundation of effective care

According to Michael Waglay, Manager of Community Peer Programs at The Neighbourhood Group Community Services, many of these patients lack trust in the health care system due to stigma and negative experiences. “Peers really help people receive the care that they need because they are able to instill more trust and remove some of those barriers,” he says.

This helps patients feel safer to disclose experiences like domestic violence or mental health challenges, helping the whole team provide more holistic care.

Compassionate care when people need it most

Patrick Esenerwa, peer support worker, recalls a patient who was experiencing suicidal ideation and paranoia. Recognizing they needed a quiet space, Patrick coordinated with the lead nurse to find an empty room where he could keep the patient company while they waited for a doctor. He got the patient something to eat and was even able to help them contact their mother, who came to the hospital.

For Patrick, compassionate and effective care like this is essential. “We bring a different kind of support that’s needed in the emergency department, especially considering the pressure the nurses and doctors go through,” he says.

Dr. Chan echoes that sentiment, saying, “Now that I’ve seen the peers in action, I simply cannot imagine working without them.” It’s impactful for the peers too, who often continue to build their careers in social work or auxiliary health care. “There’s intense stigma against being homeless, having substance use issues, having mental health issues,” Michael says. “With the peer program, a lot of their experiences that are so intensely stigmatized have become something of value. That is a very validating experience.”

No one ever changed the world on their own but when the bright minds at UHN work together with donors we can redefine the world of health care together.