Approximately 0.4 per cent of Canadians are affected by Parkinson’s disease – a progressive disorder that affects movement, balance and coordination. The risk for developing Parkinson’s disease increases with age. (Photo: Getty Images)

A study led by Dr. Anthony Lang, a Senior Scientist at University Health Network’s Krembil Brain Institute, found that the development of severe motor complications associated with medications for Parkinson’s disease does not depend on the type of medication that a doctor initially prescribes.

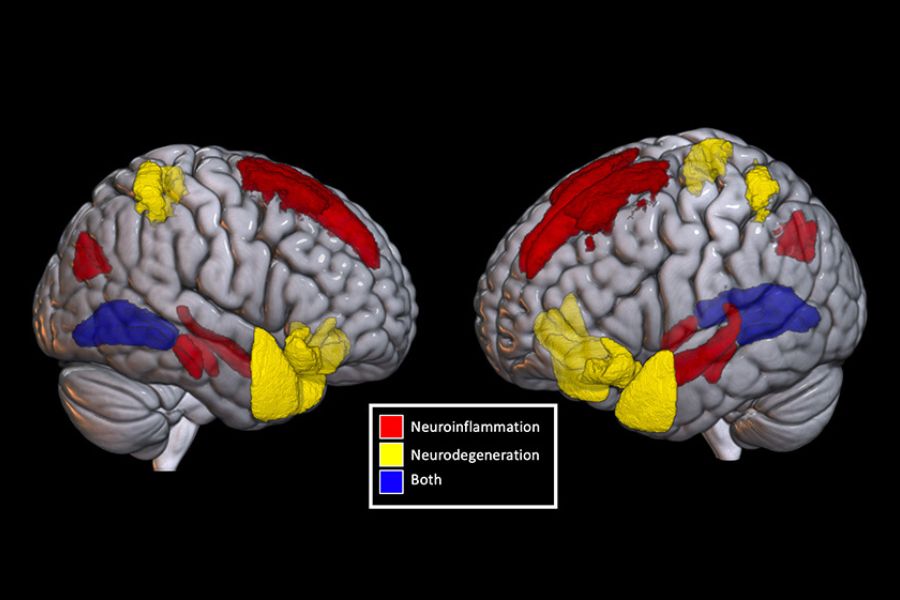

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive brain disease marked by uncontrollable movements, such as shaking. The disease results from a loss of neurons that produce dopamine – an important chemical messenger in the brain.

Parkinson’s disease is typically treated with levodopa, a drug that is converted into dopamine in the brain. Although it is highly effective, this drug often causes motor complications of its own, particularly in younger individuals.

For this reason, doctors often use a dopamine agonist – a drug that mimics dopamine activity in the brain but carries a lower risk of motor complications – as a first treatment for younger patients, before prescribing levodopa.

Despite dopamine agonists’ lower risks of motor complications for younger individuals, these drugs have important behavioural side effects and it is unclear whether initial treatment with a dopamine agonist meaningfully delays the disabling motor complications caused by levodopa.

To address this gap in knowledge, the research team examined patients who underwent deep brain stimulation surgery at Toronto Western Hospital between 2004 and 2022. Deep brain stimulation is a surgical treatment for Parkinson’s disease that is typically recommended when drug-induced motor complications become a source of disability.

Of the 438 patients examined, 312 were first treated with levodopa and 126 first received a dopamine agonist. Across groups, half of the patients had lived with Parkinson’s disease for 10 years or more before they underwent deep brain stimulation for disabling motor complications.

The team found no association between the type of medication first used and the time it took for individuals to develop disabling motor complications.

“This is the only study to date to examine the link between the particular Parkinson’s disease medication first used to treat the disease and the time to development of serious motor complications that warrant surgery,” says Dr. Lang, who is also a professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto.

“These results are important because there are still practitioners who initiate dopamine agonists first, especially putting younger patients at risk of neuropsychiatric side effects, with the incorrect belief that they are delaying the need for deep brain stimulation surgery in the long run.”

Dr. Diana Olszewska, a former Movement Disorders Fellow at Toronto Western Hospital and the first author of the study, says the findings reveal the need for more studies and novel treatments.

“While more research is needed to determine how these drugs affect patients’ quality of life before symptoms worsen, it is clear that there is a real need for new therapies that carry lower risks of complications.”

This work was supported in part by donors to UHN Foundation.