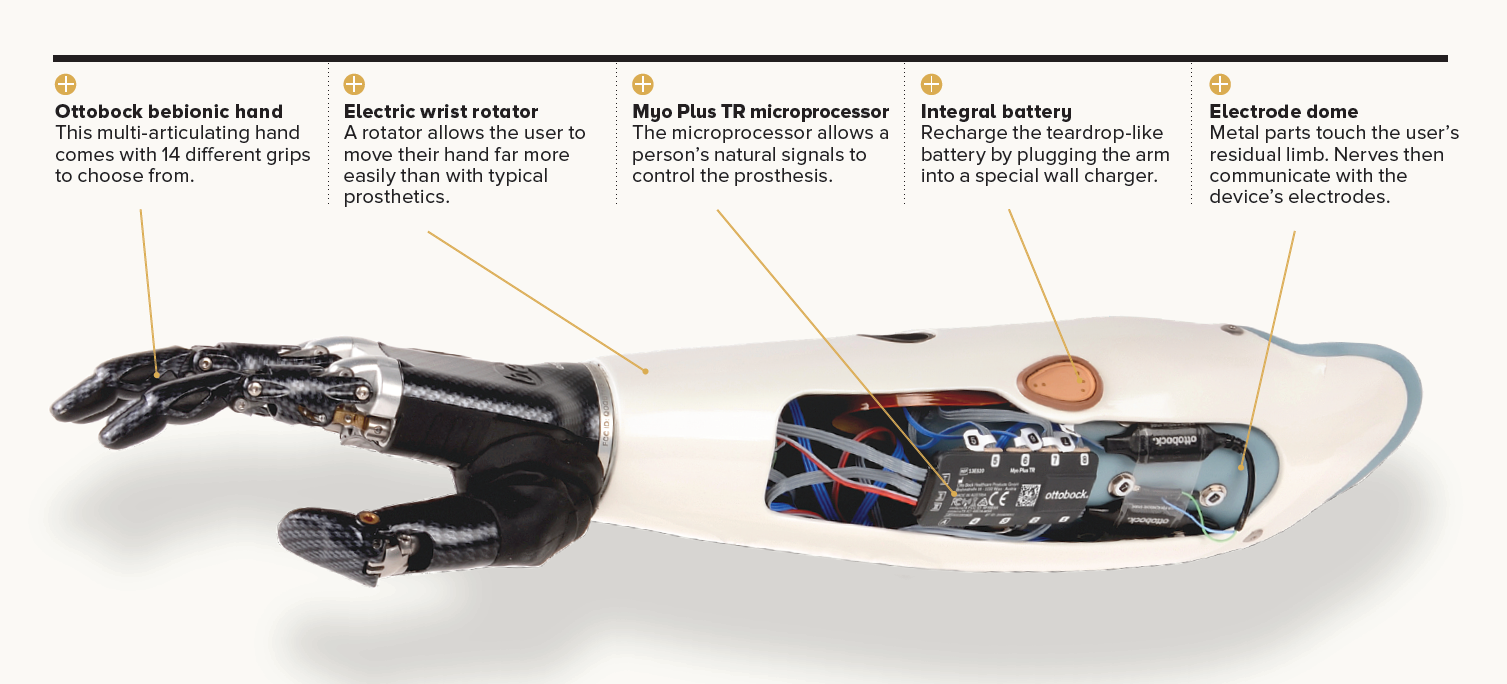

Photo courtesy of Ottobock (Myo Plus TR Prosthesis).

A new kind of artificial hand, combined with an innovative operation, is helping amputees use their limbs again.

By Sharon Oosthoek

“Can you imagine not having a hand? How would it affect your daily life?” asks Dr. Heather Baltzer, a plastic surgeon in the Sprott Department of Surgery and Director of the Hand Program at University Health Network. As a prominent Canadian hand surgeon, she’s treated many patients with a loss of digits or hands and knows just how impactful this can be on a person’s life. While prosthetic hands are helpful, patients who use them still struggle to do simple tasks, such as picking up a glass of water.

While Dr. Baltzer would prefer if everyone were able to keep the limbs they were born with, that’s not realistic: traumas from causes such as workplace and construction injuries continue to happen, leading to nearly 5,000 Ontarians with severe lower arm and hand injuries per year. One of her focuses now is on getting those with amputations increasingly sophisticated prosthetics.

A better prosthetic

Most prosthetics today are what Dr. Baltzer calls “body powered.” Patients move their elbows or upper arms in a certain way to mechanically operate a cable in the prosthetic. This lets them do one thing at a time, such as open or close their fingers, but not rotate the wrist. “It’s Civil War-type technology,” she says. “But it’s still used today.”

Dr. Baltzer works in collaboration with a rehabilitation medicine specialist, Dr. Amanda Mayo, to give people something better: the myoelectric prosthetic, an artificial hand that takes signals from a person’s muscles and transmits them into multiple movements at once. With this hand, people can lift a beverage to their lips or even carry a suitcase.

Limb fixer. Dr. Heather Baltzer is one of the top hand surgeons in Canada. Photo by Tim Fraser.

Specialized surgery

Not everyone has access to the myoelectric prosthetic. For someone to get one, they must undergo a special procedure Dr. Baltzer performs. This surgery prepares a patient’s body to work with the device, because after any amputation, severed nerve endings continue to grow “like a salamander’s tail,” she explains. The nerve endings form painful little balls called neuromas, which make it difficult to wear any kind of prosthetic.

Dr. Baltzer surgically removes these neuromas and redirects the nerve endings to a muscle in the remaining upper arm, which boosts the muscle’s electrical signal. (Muscles and nerves work together to generate electricity that allows bodies to move.) That electrical signal can be detected on the skin and is then picked up by a sensor inside the prosthetic. “So, when your brain tells your hand to flex, even if it’s not the muscle that was supposed to make your fingers flex, it gives that signal,” says. Dr. Baltzer.

More sensory feedback

While myoelectric hands are a step up from the older models, they’re still not perfect – they can’t give sensory feedback to the brain, which makes it harder to grasp something delicate, like an egg, without crushing it.

So, Dr. Baltzer is bringing together several Toronto-based experts to design inexpensive prosthetics that meet this need. “Sensory feedback will make patients feel that this is really their hand,” she says. “You need to look toward the future. You need to offer hope.”

Injury impact

227,000 Canadians living with a limb or extremity amputation (Source: Active Living Alliance)

This article originally appeared in the Sprott Department of Surgery magazine.