Ms. Wood, who lives in Toronto with her husband, also went last year for a brain scan to be used by the same group of Krembil scientists. The team is led by world-leading Parkinson’s disease neurologist Dr. Anthony Lang, director of the Edmond J. Safra Program in Parkinson’s Disease and holder of the Lily Safra Chair in Movement Disorders. Ms. Wood had to travel to Buffalo, N.Y., for the scan because the particular machine used in the study is not available in Canada.

It’s a lot to give and do for research. But for Ms. Wood, it’s a way of fighting back against the disease she was diagnosed with five years ago.

“It took about a year to find out what was wrong with me, but in the end, the conclusion – which I had already suspected myself– was that I have Parkinson’s disease,” says Ms. Wood, who is 56 years old and recently retired from an executive role in a national, not-for-profit land conservation organization.

The research project Ms. Wood contributed to last year – she’s been involved in five other previous studies – is called the Systemic Synuclein Sampling Study or S4, for short.

The object of the study is to identify the best biological indicators for Parkinson’s disease by tracking the levels of a protein called alpha-synuclein. This normally occurring protein, which is believed to play an important role in the development of Parkinson’s, has been found in concentrated clumps in the brain cells of people with the disease, within substances called Lewy bodies.

“There are suggestions that Parkinson’s disease doesn’t begin in the brain at all, and that by the time patients present with the disease, we may be trying to treat them too late, because the disease is already well established,” says Dr. Lang, the S4 lead investigator at Krembil. “So if we can define the presence of alpha-synuclein in peripheral systems where the disease might have started, then that could lead to an earlier diagnosis of Parkinson’s, as well as the development of treatment to slow the progression of this disease.”

There are other studies focused on the presence of alpha-synuclein in a specific site of the body such as the colon or the skin. S4 is the first study to look at alpha-synuclein in multiple parts of the body. The study, which is enrolling 80 participants, including 20 for the control group without Parkinson’s, is looking at patients across all stages of the disease.

At Krembil, S4 researchers are also experimenting with various imaging techniques and assays to figure out the best methods for spotting alpha-synuclein as a biomarker for Parkinson’s disease.

“We are looking at all these different regions within a given individual for critical information about the distribution of alphasynuclein throughout the body of somebody with Parkinson’s disease, then we are correlating this information with the brain scan, which tells us how advanced the disease is,” explains Dr. Naomi Visanji, who, along with Dr. Connie Marras, is working with Dr. Lang on S4. “By looking at patients with different stages of Parkinson’s, we will have a clear picture of how alpha-synuclein in systems outside the brain changes, according to the progression of the disease.”

There are currently no biomarkers for Parkinson’s, and the disease is diagnosed based on a clinical assessment of symptoms such as trembling, stiffness in the limbs or neck and limited facial expressions. Some doctors confirm their diagnosis with a brain scan that looks at levels of dopamine, a neurotransmitter whose presence slowly diminishes in people with Parkinson’s.

“The field is moving toward clinical trials of drugs that will stop the disease in its tracks,” says Dr. Visanji. “It would be nice to see biomarkers that indicate if alpha-synuclein has stopped aggregating after a patient has taken a certain drug or if it’s actually accumulating even more.”

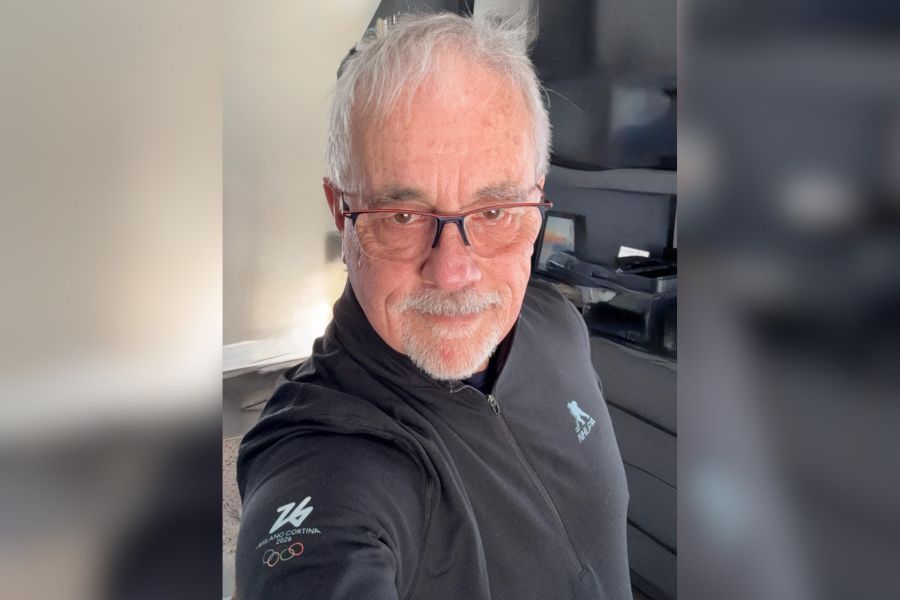

Krembil is looking to sign up 12 S4 participants. So far, six people have enrolled, including Mike Clare, a former high-school history teacher whose wife has Parkinson’s disease.

Providing samples and travelling to Buffalo for a brain scan presented some inconvenience and discomfort, and the results of S4 are unlikely to yield direct benefits for him or his wife. But Mr. Clare, who like Ms. Wood lives in Toronto, says he’s happy to be part of this novel – and hopefully groundbreaking – study into a disease that still remains a medical mystery.

“I could get really angry that my brilliant, gorgeous wife has this disease, but what good would that do?” he says. “Taking part in this and other studies gives [us] a way to give back and maybe help prevent future generations from getting this terrible disease.”