Dr. Richard Ward, Medical Director of the Red Blood Cell Disorders Clinic at Toronto General Hospital, collaborated with the Princess Margaret team to cure an adult of sickle cell disease. (Photo: Visual Services, UHN)

University Health Network (UHN) has cured an adult of sickle cell disease with a stem cell transplant from a sibling donor, freeing the patient forever from constant blood transfusions and medical complications related to the illness.

“The main therapies for adult sickle cell patients are those that treat symptoms and attempt to control disease, such as transfusions, pain medication or even hospital admissions for extreme pain,” says Dr. Richard Ward, Medical Director of the Red Blood Cell Disorders Clinic at Toronto General Hospital (TGH), adding that a transplant represents a cure for a life-long, debilitating disease.

The stem cell transplant took place about six months ago, with the collaboration of the TGH Blood Disorders Program and the Blood and Marrow Transplant Program at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, under the direction of Dr. Rajat Kumar, Head of Malignant Hematology at PM, and the stem cell transplant team.

It was a first for UHN. Transplants for people with sickle cell disease, adults as well as children, have been done in Calgary, SickKids, and select centres in other countries.

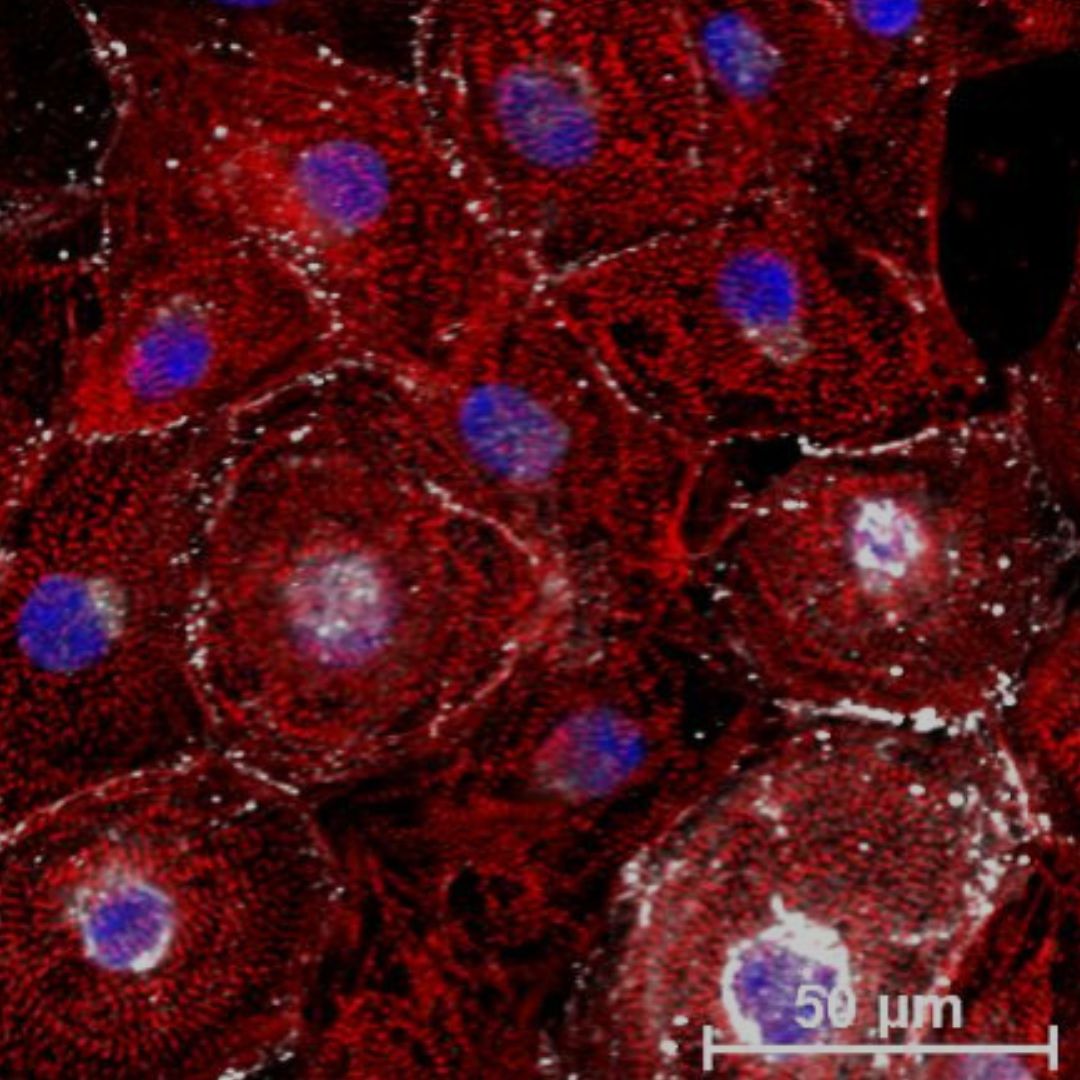

As a result of the transplant, the patient, who wishes to remain anonymous, can produce normal, red blood cells instead of the sickle-shaped blood cells of the disease. Abnormally shaped blood cells become sticky, and clumps of them block blood flow, causing severe pain, organ damage, and sometimes stroke.

“This is huge for me,” says the patient. “Getting the transplant has made the biggest difference for me. I can do so much more, I have a new sense of energy.

“I don’t feel sick. I have freedom from sickness.”

The patient had been hospitalized several times in high school and university, for acute chest pains with difficulty in breathing, pneumonia, and a stroke.

After the most recent follow-up test at the end of March of this year, Dr. Kumar reported that the patient was cured, with no evidence of sickle cell disease.

Dr. Richard Ward describes this new option at UHN for patients with sickle cell disease as “transformative.

“Every patient should be made aware of this new standard of treatment for sickle cell disease. It can change lives. Patients don’t have to go to the hospital because of their severe pain, and they can stop taking pain medications. They can live normal lives,” says Dr. Ward.

He adds: “As sickle cell disease predominantly affects people with African ancestry, this treatment is especially helpful to a racialized and often marginalized population.”

Currently, to be eligible for the stem cell transplant at PM, patients must have a sibling who is a 100 per cent immunological match in order to provide the blood stem cells to make new and healthy red blood cells in the patient. A perfect match ensures that donor and recipient tissues are compatible, and that donor cells will not be attacked and rejected.

Donors who are not perfect matches may be considered at a later date.

To prepare for the transplant, a patient suffering from sickle cell disease first receives a “conditioning” regimen of immuno-suppressive drugs and a one-day, low-dose course of radiation. This reduces the patient’s immune response, and prepares the body to accept the new donor cells.

Dr. Kumar notes that the immune-suppressive drugs used in this transplant are not as harsh as the chemotherapy medication used for patients who go through a similar bone marrow transplant for blood cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma.

This gentler approach to transplant has made it possible to now offer this therapy to adults, for whom transplant is riskier than in children, as their tissues and organs may have been damaged by sickle cell disease far more than those of a child with the same illness.

During the transplant, donated blood-derived stem cells are injected into a patient’s vein, and the donor’s stem cells begin to replace the patient’s bone marrow. These stem cells produce red blood cells with normal hemoglobin, which play a key role in oxygen delivery and maintain the shape of red blood cells.

After the transplant, the patient is on anti-rejection drugs for one to two years.

For the first patient at PM, who is just starting out in his career, the transplant has meant a future without constant transfusions, clinic appointments, pains in his legs or back, and tiredness from anemia.

“Now I can hardly sit still,” he says. “I always want to be up and about.

“For me, the sky’s the limit!”