Dr. John Granton, UHN Intensive Care physician, says capacity is always an issue on the Toronto General Hospital MSICU where there are still patients from Wave Two. (Photo: UHN)

By the time a COVID-19 patient lands in the Medical Surgical Intensive Care Unit (MSICU) at Toronto General Hospital, some things are clear. The stay will be long, maybe months. A machine, known as ECMO, is likely involved.

And, this is the last shot at survival.

“If they didn’t get ECMO they would die,” Dr. John Granton, one of UHN’s Intensive Care physicians, says of the machine that does the job of the lungs to allow them to rest and recover from COVID-19.

ECMO siphons off a portion of a patient’s blood and passes it through a circuit pump, removing carbon dioxide, then gives it oxygen before returning it back into the bloodstream through another vein.

The survival rate for those who require ECMO, which stands for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation?

“It really depends on who you’re putting on it,” Dr. Granton says. “An older person with comorbid conditions has a much worse chance. The younger person has a better outcome.

“So, the world literature would suggest that about 60 per cent survive.”

The TGH MSICU is a regional centre for ECMO, meaning the sickest COVID-19 patients get sent here as a last chance. It involves a lot of paraphernalia – tubes, centrifugal pump, cannulae, artificial lung – and a lot of staff to operate – perfusionist, respiratory therapist (RT), nurses, doctors.

On April 19, the TGH MSICU surpassed 25 patients on ECMO, a figure not reached in the first or second wave of the pandemic. It was decided a staff physician must be on site around-the-clock to support ICU staff and handle outside referral consults from hospitals looking to send their patients here.

Dr. Granton is one of the staff physicians that is doing the overnight call. This is his first 24-hour shift since he was a young resident.

“I’ll put down a little bed in the office to nap a little later during the 24 hours,” he says.

By 7 a.m., he’s in a conference room on the 11th floor for shift “handover.” A dozen tables form a large rectangle around the room to allow for physical distancing for the 15 or so masked charge nurses, fellows, residents, and doctors spread around the room.

This is where overnight patient status is reviewed by the four ICU teams. Today, Team C has 12 non-COVID ICU patients on the second floor. Teams A and B, take care of the 34 patients on the 10th floor ICU, where all but a few have COVID. Team D helps with consults, Critical Care Response Team calls and supports the teams working on the COVID floors.

On this day, 29 patients are on ECMO, a grim, new record.

“This wave really shouldn’t have happened,” Dr. Granton says, not with any anger or bitterness in his voice but more a weary disappointment. “We don’t seem to learn from other countries experiences.

“It’s an anticipatory sport, and like any game you have to anticipate the next move and we didn’t. You just had to look at Europe and say okay, this is what’s coming this is what we have to do.

“And we have to do it ahead of it actually happening otherwise you’re just reacting.”

Each speaker in the meeting is deliberate and unfaltering in their stark recitation of patient details. Hemoglobin levels and white counts, vomiting and mouth bleeding, Heparin and Lasix, cannulation and proning.

Snippets of patient back stories also emerge: “Patient is a construction worker…wife, one son, also both COVID positive…he is suffering respiratory failure…”

“Patient…factory worker…intubated…”

Dr. Granton is at one of the portable computers, scrolling through each patient record displayed on monitors for all to see. The news for some patients is dire: “right lung destroyed; she’s not doing well; right lung completely destroyed.”

“It’s a blue-collar disease, he says. “These are the people who work in the factories. That’s where we need to focus our efforts in vaccination and provide paid sick leave.

“Workers get infected because their workplaces are infected.

“If we dealt with these important communities we wouldn’t have as big a problem, so going into the Amazon warehouses and the post office sorting facilities and just vaccinating right away, just like we did for long-term care.”

After the handover, Dr. Granton tours ICU units on the second and 10th floors to see how everyone is doing. Patients and staff. In addition to his day job, he shares oversight of UHN’s Occupational Health Services. He knows some staff are hanging on by a thread – if there’s any thread left.

And, some are already leaving the profession.

“I’d say the big stress points are the Emergency nurses, managing whatever comes in, same with the docs, and then the ICU nurses,” he says. “For the ICU nurses and the RTs, the perfusionists, physiotherapists and other members of our interprofessional team – it’s just unrelenting.

“We come in, we do our rounds. We go into the room, we leave. The nurses are there at the bedside, doing the work, those are the people I think are having the hardest time, they’ve got the toughest job compared to us.”

As Dr. Granton continues his ICU tour, strains of music can be heard. It’s coming from some of the rooms with ECMO patients. Everything from opera to country. It’s hard to know if the music pierces the awareness of these intubated souls in medically-induced comas.

He stops to watch the “proning” of a patient – turned onto their stomach, arms in a “swimmer’s position” where they will lie for up to 16 hours. Proning helps distribute breathing more evenly and protects the lungs. The process takes six staff.

By 9 a.m., Dr. Granton is at the MSICU Nursing Station for morning “huddle.” This is a quick stand-up meeting to review performance indicators and raise any practice issues. Today, it’s an opportunity to acknowledge and welcome five staff recently redeployed from the cardiovascular ICU.

A question arises. What happens when the ICU hits 30 ECMO patients? The answer comes back “personnel would be the issue” – not enough staff. Another query about another ICU being created on the sixth floor. The answer – “TBA.”

Capacity is a never-ending issue on the ICU.

“What you’ll see in the unit is we still have patients from Wave Two, and so they’re occupying space,” explains Dr. Granton. “They’re here for the long haul. They don’t leave the ICU very fast.”

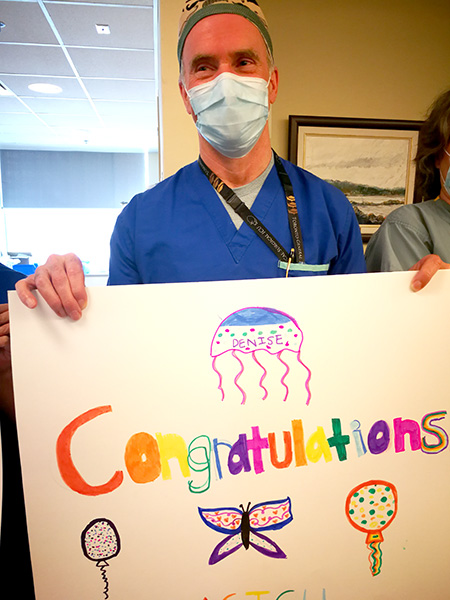

Later in the morning, there is a welcome celebration. A colleague has been voted one of Canada’s top nurses by Hospital News. Dr. Granton is front and centre with the team, holding up a sign saying “Congratulations” to honour the exceptional contributions of MSICU Nurse Manager Denise Morris, who is briefly overcome with emotion at the news. She musters a heartfelt speech of thank you to her team.

“Keep doing what you’re doing, and keep taking care of each other,” Denise says.

As soon as the celebration ends, Dr. Granton finds a quiet room to return the call of a colleague at Mount Sinai. They have a pregnant woman with COVID who may need ECMO. If there’s a silver lining in this pandemic, it’s province-wide cooperation.

“There’s been a systems approach to healthcare, like, how to allocate resources on a systems level, and collaboration and cooperation on a system level,” Dr. Granton says. “Getting teams to work together that hadn’t worked together.

“Something good will come of that. We’ve been very proactive in sorting stuff out.”

With brown bag lunch in hand, Dr. Granton hustles up to his office in time for a 1 p.m. MS Teams call he is chairing with nine colleagues. For 90 minutes, they discuss treatment options for one of Granton’s non-COVID patients. They run through several scenarios. As soon as the call is done, he heads down to the ICU to visit the woman and lay out the options. They will take a wait and see approach over the weekend.

By 4 p.m., his first scheduling conflict arises. He is needed at the bedside of a COIVD patient on ECMO who has been approved for an experimental stem cell treatment. Dr. Granton is the Principal Investigator of the trial – evaluating the use of placental derived cells in COVID-19 infection – a strategy that was the brain-child of Dr. Jonas Mattsson at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

That procedure means he will miss the retirement send-off for an ICU nurse colleague who has been at TGH since 1985. Turns out he won’t be missing her for long. Unable to abandon her colleagues in the middle of the pandemic, she announces she has signed on to be available for on-call shifts.

By 4:25 p.m., Dr. Granton is back in the 11th floor conference room for another handover. Many of the same faces from the 7 a.m. meeting are present, along with new members for the night shift. The patient details are much the same.

The handover wraps at 5:20 p.m. with Dr. Granton asking what everyone wants for dinner, he’s buying.

Then it’s back to his office for another outside consult about a patient. The pace is relentless. Down time non-existent. Yet Dr. Granton appears unfazed. It is the work he loves. When asked what he would like the outside world to know about what it’s like inside the walls of TGH he replies without hesitation.

“How amazing our team is,” he says. ”And how they pull together, and how they look after each other.

“They’ve got each other’s backs. They’re all patient-focused, this is their passion and they see this as being really important and they just do whatever it takes.”