Alzheimer’s patient Carine Scott and her husband, Henderson, steal a moment outside Belmont House, a Toronto-based retirement home.

At age 80, Cairine Scott has a glow that most people would envy. Her eyes twinkle beneath a sweep of fine silver hair, and she chuckles at the old stories her 86-year-old husband, Henderson, brings up about the rich lives they’ve led together. During an afternoon lunch in June, Cairine looks flawless in a textured red-and-green jacket. She’s also wearing elegant green-gold earrings and sporting a fiery-red manicure, all of which go well with her hobby of painting brightly coloured canvases, many of which decorate their room.

Cairine, a former elementary school teacher, has certainly led a full life, but she now has trouble remembering the life she’s lived. Cairine has Alzheimer’s disease, and although she follows the lunchtime conversation, she may not remember today’s meal, nor the visitors who ate with her. After lunch, she shows off the library she designed a decade ago for the residents of Belmont House, one of Toronto’s best-appointed retirement homes, where she and her husband, a former university professor, live. A plaque on a shelf recognizes Cairine for her work on the library. Today, it’s getting harder for her to read any books, or even spell her own name.

People with dementia can still lead vibrant lives, no matter their diagnosis. Yet the sharp rise of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia is deeply concerning, especially as the population ages. More than half a million Canadians now live with some form of dementia, and 65 per cent of those diagnosed after age 65 are women. This number is expected to rise to 937,000 by 2031, according to a report from the Alzheimer Society of Canada, and combined costs to the healthcare system and to individuals will balloon to $16.6 billion. It’s a similar story elsewhere.

Alzheimer’s is clearly a major health challenge, if not already a crisis. Yet a cure remains elusive. Countless dollars have been spent on finding a remedy ever since German psychiatrist Dr. Alois Alzheimer first identified the disease in 1906, while billions would be saved with the right treatment. So, what’s the issue?

More research required

One problem is that researchers still don’t fully understand the disease, says

Dr. David Tang-Wai, co-director of University Health Network (UHN) Memory Clinic at Toronto Western Hospital. “We have ideas and theories,” he says. Researchers know that a brain with Alzheimer’s is characterized by scattered clumps of two specific proteins, called beta-amyloid and tau, which prevent nutrients and signals from reaching brain cells. But experts don’t yet have a handle on what triggers the disease in a healthy brain. “How do you go from a normal brain to the beginnings of Alzheimer’s disease? We know pretty much everything after that, but what is that process?”

Without a clear understanding of the underlying biology of the illness, there isn’t much chance for a cure. Meanwhile, an Alzheimer’s diagnosis is an imperfect process. “Of the top 10 [causes of death] recognized by the WHO, Alzheimer’s disease is the one for which we don’t have a clear-cut diagnostic technique,” says Dr. Donald Weaver, co-director and senior scientist at the Krembil Brain Institute, who doesn’t mince words about the uphill battle dementia researchers face. “And even if we were able to diagnose it, we couldn’t treat it.”

Trouble finding treatments

It’s not that companies haven’t been trying to find a cure. Pharmaceutical businesses have poured billions into the search, and their efforts have yielded some results. Medications such as Aricept (Pfizer), Exelon (Novartis) and others symptomatically help problems with cognition, memory and the ability to do basic activities like bathing and eating. They do this by increasing the amount of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in the brain, which tends to decline with Alzheimer’s disease.

While this helps, it’s far from a cure. “If you have strep throat, you can take Aspirin,” says Dr. Weaver. “It will help with the pain and the fever, but you still have strep throat.” What we don’t have, he says, are what scientists call “disease-modifying drugs.” Rather than treating the symptoms, these Holy Grail drugs would stop the pathological changes in the brain that lead to the disease in the first place. A conservative estimate is that first-year sales of such a drug would be around $10 billion. But it’s a tough jackpot to win. “The last 196 trials of disease modifying drugs have all failed,” says Dr. Weaver.

Part of the reason for this is that while companies have worked on the right drugs, they’ve been working with the wrong timelines, explains Dr. Weaver. The brain is made mostly of fat, but proteins play an important role in how neurons signal to each other. For decades, Alzheimer’s drug research focused on a certain protein called beta-amyloid, which forms harmful plaques when it clumps together with other proteins. These plaques are toxic, preventing nerve signalling and destroying brain cells. But the bet on beta-amyloid was flawed. “A number of people developed agents that prevent the clumping, but when they were given to people, they did nothing,” he says. Researchers now realize that beta-amyloid likely begins to clump, or “misfold,” 20 years before patients show their first symptoms. This means the drugs might have been effective at one point, but they’re two decades too late.

After so many high-profile failures, these pharmaceutical giants are now pulling the plug. Pfizer made headlines when it halted its search for new Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s drugs in January 2018. In June of that same year, AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly stopped a trial of a drug intended for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. The news is devastating for patients and their families, who see drug trials as a source of hope.There is still progress being made on a cure, however.

Dr. Weaver and his colleagues are working on new possible disease-modifying drugs at Krembil – and they refuse to give up.

Discovering Alzheimer’s early

What we do know about Alzheimer’s, the most common type of dementia, is that affected brains look different than healthy ones. Plaques and tangles created by the clumping of beta-amyloid and tau proteins result in cell death. Brains lose tissue and shrink in size.

For many years, examining the brain post-mortem was the only way to diagnose Alzheimer’s. Diagnosis is done on living patients today, but it’s tricky. Doctors typically administer a test on memory, cognition and attention, which they score themselves using paper and pen – paper that will be buried in a file folder afterwards. At Krembil, Dr. Tang-Wai and a group of University of Toronto researchers are using new technology to come up with a faster, more nuanced test – one that can simultaneously gather data to lead to future discoveries.

The new Toronto Cognitive Assessment (TorCA) was developed by three principal researchers, including Dr. Tang-Wai, and other experts from geriatric medicine, geriatric psychiatry, neuropsychology and neurology. Within the 30 minutes it takes to administer the test on a tablet, the TorCA instantly compares the patient’s score with that of healthy subjects in Toronto in their age group, showing a star if they’re below a certain range – helping their doctor to diagnose them quicker. More significantly, the test also does on-the-fly data capture, gathering and sharing details from patients across Toronto with researchers around the city. One of the main obstacles slowing down global Alzheimer’s research is that researchers must ask subjects’ permission to use their data anew with every study. The TorCA – which has been rolled out at Baycrest, CAMH, Sunnybrook and UHN – asks permission just once to store data for future research. It also removes identifying personal information. This will create a data goldmine that could lead to untold new breakthroughs. “Most of our advances in almost everything in medicine are because we study a lot of people,” Dr. Tang-Wai explains.

To illustrate, take the clock test. Drawing a circular clock face is an old and simple way to screen for dementia. A correctly drawn clock is typically a sign that someone is dementia-free. What if a subject draws a perfect clock, however, but in an odd way – drawing the hands first, then adding the numbers, and finally the circle at the end? A paper test can’t record this level of detail, but an electronic one can. That information would be added to a data set of other subjects in the city who also draw their clocks that same way. We’d be able to find out what else these subjects have in common – and perhaps reveal something new about the earliest, subtlest changes inside brains affected by dementia. Early diagnosis helped Cairine. Her family doctor suggested she take a cognitive test in 2010 after he noticed she showed some confusion during a routine appointment, something so slight her husband hadn’t picked up on it. Cairine was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and brought under the care of Dr. Tang-Wai and Krembil. Ultimately diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, she has been taking three drugs that have collectively slowed the progression of her disease. “I don’t forget every last thing,” she says. Her illness has had a “gentle slope” over years, says Henderson, giving them both time to adjust. At Krembil, they feel they’re not only plugged into the latest discoveries, but also treated with compassion, says Henderson. “Dr. Tang-Wai doesn’t just focus on the drugs. You feel like you’ve met with a psychotherapist,” he says.

Finding a cure

If Dr. Tang-Wai is working to diagnose patients earlier, Dr. Weaver is set on finding new medications to treat them. He acknowledges his “likelihood of failure is 99 per cent,” which may be why he’s working on multiple drugs at once.

While so many failed earlier trials focused solely on beta-amyloid protein, Dr. Weaver is working on a drug that will act on the tau protein. When healthy, tau transports essential nutrients in the brain; when it clumps or tangles, it prevents nutrients from being delivered and kills cells, resulting in the brain changes of Alzheimer’s. Tau is promising because researchers believe it might respond to treatment even after a patient has already experienced symptoms.

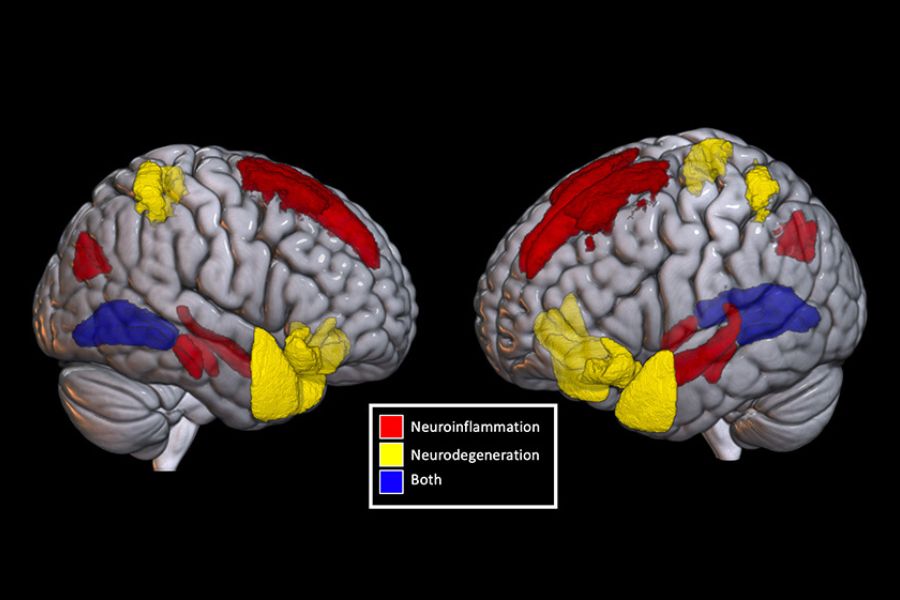

Dr. Weaver, who also holds a chemistry Ph.D., used computer modelling to analyze tau’s distinct shape and has tested about 12 million chemical compounds to find some that can block the deadly changes in tau’s shape before it does too much damage. Along with French pharmaceutical company Servier, he is working to turn the compounds he’s found into drugs for the market – and for future patients. Inflammation is another new frontier in Alzheimer’s research that scientists are excited about, and Dr. Weaver is no exception. The body’s inflammatory response is a key part of healing, but chronic inflammation is now thought to be the cause of many kinds of illnesses, from allergies to cancer. Inflammation may be a factor in Alzheimer’s when it involves the brain’s glial cells – support cells that cluster around the neurons and help them function. Although the cause is not yet clear, these support cells can change and produce toxic, inflammatory chemicals that kill neighbouring neurons. Dr. Weaver is working on a drug that will dampen the inflammatory response. While traditional drug companies may be giving up on Alzheimer’s research, doctors and researchers at Krembil certainly aren’t – and neither is Cairine. Far from slowing down, she started painting recently, both abstract canvases and pictures of animals. They’re neon yellows and acid pinks. She also does everything her retirement home offers, from music appreciation to dance. “I have to recognize how I am,” she says. But that doesn’t mean she’s going to let that define her.

This article originally appeared in the 2018 issue of Krembil magazine. Read it here.