Patients entering the doors of a UHN site are often seeking care for their physical well-being. Yet many grapple with undetected or unaddressed mental health challenges, which can surface during their hospital stay and worsen their physical health.

It’s an issue with profound ramifications for their long-term health: people with physical health concerns are at an increased risk of developing co-occurring mental health issues – such as anxiety and depression – which can lead to more frequent hospitalizations and reduce life expectancy by as much as 15 to 20 years.

UHN’s Inpatient Consultation-Liaison (C-L) Psychiatry Service plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between physical and mental health care, providing as-needed support to inpatient medical and surgical units.

“We float around the hospital helping folks with the mental health aspects related to other medical issues,” says psychiatrist Dr. Alan Wai, a member of Toronto General Hospital’s C-L team. “It’s this unique space that requires us to be involved with peoples’ medical care and their care providers, while applying a mental health lens to the situation.”

A typical day for Dr. Wai can take him from Cardiology to the Transplant Unit, the HIV Clinic to the Emergency Department (ED). He’ll be called on by medical teams to support patients displaying conditions such as delirium, mood disorders, suicidality, or agitation – which may be pre-existing or emerge during a patient’s hospitalization at UHN.

Communications skills are essential to forge a connection

These conditions could be a patient’s response to a challenging diagnosis or stem from physical symptoms, such as pain or fatigue, causing significant emotional distress and affecting daily life.

“Sometimes patients ask for us,” says Dr. Wai. “But sometimes they don’t, and when we show up it can be jarring for patients and families who didn’t ask and who’ve never met with psychiatry.

“As the bridge between physical and mental health, we have both the responsibility and opportunity to make every encounter therapeutic and meaningful.”

Patient consults require resourcefulness, adaptability and technical knowledge, such as understanding how psychiatric medication choices can affect a patient’s medical illness and how medical treatments can impact psychiatric symptoms. Communication skills are essential to help forge connections with highly vulnerable patients they have just met, and the medical teams they collaborate with.

Treatments provided will include pharmacology, psychoeducation and referrals to other organizations, as well as brief, supportive psychotherapy to help patients cope with their distress.

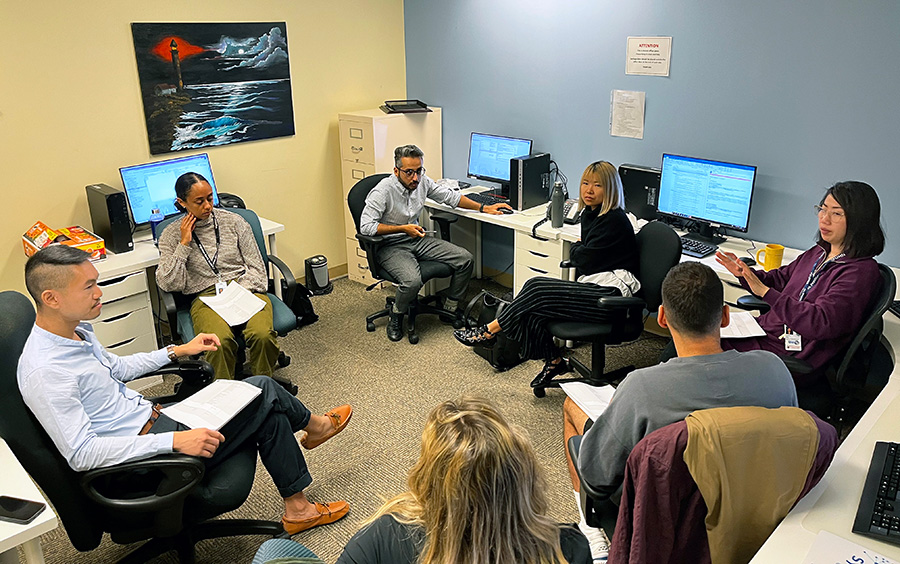

Dr. Wai started a recent day with a 9 a.m. team meeting with three residents, a fellow, a medical student and Linda Liu, a clinical nurse specialist. C-L is team-based, and the learners play a critical role: conducting initial assessments, proposing diagnoses and treatments for team review and providing followup care.

The team reviews the day’s patients, which include overnight arrivals. Dr. Wai gives advice on how to engage a patient declining to take their medication, or how to respond when a patient’s family insists on a medically unsupported treatment. He stresses the need to validate feelings, and to build bridges between the medical team, the family and the patient.

The team divides the list of morning consults and regroup in the afternoon to present patient updates, conduct case-relevant teaching and then collectively visit the day’s new patients.

On this day, that includes an elderly patient who had a stroke during a heart diagnostic procedure. The patient is recovering physically, but is now swinging between hyperactivity and extreme drowsiness and confusion.

Post-stroke delirium is suspected, a sudden and severe change in brain function linked to worse outcomes for older adults in hospital. Given the patient’s history, they recommend a followup CT scan to better understand the cause.

Next stop: General Internal Medicine. An elderly patient with a history of psychiatric illness suffers from cellulitis, a painful bacterial skin infection that causes swelling. They exhibit forgetfulness and made a comment about suicide, alarming the medical care team.

Dr. Wai and the C-L team assess the seriousness of the suicidal expressions and recommend recalibrating the patient’s psychiatric medication to reduce mental fogginess.

They end their rounds in the ED. A young adult who attempted suicide and suffered heavy blood loss has been stabilized medically after receiving a transfusion from the medicine team. The patient is now quiet and withdrawn, but remains high risk.

The C-L team will deliberate where the patient is best served, which may include a transfer to UHN’s Mental Health Inpatient Unit.

Additional C-L teams operate out of Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto Rehab, and Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. They often see different patient populations just by the nature of the units they service. Annually, they are called in to support more than 1,750 inpatients.

At Toronto Western, there is stronger representation from neurology, rheumatology and orthopedics. Similar to other C-L teams, the day begins with a team meeting. Dr. Richard Yanofsky is the psychiatrist on service. He’s supported by two residents, a medical student, and Edna Bonsu, a clinical nurse specialist Edna.

Today, a Code White call for a violent patient came in just as their shift starts. An agitated patient with a serious physical illness is paranoid and trying to leave the hospital. The team will provide a different anti-psychotic medication that carries calming effects and discuss other ways to calm the patient.

In the Operating Room, a patient with a history of mental health issues is refusing surgery, and not for the first time. Dr. Hawraa Almahmeed, a resident, uncovers that an epidural is the source of the patient’s anxiety and communicates this to the care team who switch to general anesthesia.

Medical student Jordan Smith visits a patient with depressive symptoms and a history of suicidality. The consult is complicated by a language barrier – the patient doesn’t speak English – and requires help from UHN’s Interpretation and Translation Service.

“It’s the perfect example of how adaptable you have to be – like a lot of things in medicine the realities on the ground are very different than the theoretical ones,” says Dr. Yanofsky. “You’ve got multiple sedating agents and a profound language barrier and you’re talking about emotionally complicated, sensitive things.”

‘It’s the spirit of the service to see if there is any way we can help’

That afternoon, the team will visit a post-op patient after spinal surgery. They have a history of managing chronic pain and mobility issues, as well as depression. Recent personal upheavals are added stressors.

Dr. Yanofsky greets the patient warmly, pulls up close to his bed and leans in, clasping the bed rail. The team circles around. They review what has happened and talk about the patient’s emotional distress.

As he speaks, Dr. Yanofsky releases his hand from the rail, allowing it to hover in proximity to the patient’s legs – a gesture filled with compassion and support.

Disarmed, the patient begins to open up. Within minutes banter blossoms within the group. Jokes fly around. Humour becomes a tool for building connections.

The team leaves with a promise to explore a potential referral to an outpatient psychiatric support program. The patient appears genuinely happy for the visit.

It’s a low-intensity consult and one that doesn’t lean heavily on the team’s specialized training or medical knowledge, but it provides a sense of gratification for the team.

In navigating the intricate terrain of patients’ physical and mental health, adaptability and empathy prove equally vital alongside medical expertise, providing solace to those in need within UHN’s walls.

“There is a therapeutic benefit to interviewing a patient, to bearing witness to what they are experiencing,” says Dr. Yanofsky.

“When we are called for a consult, it’s the spirit of the service to see if there is any way we can help.”