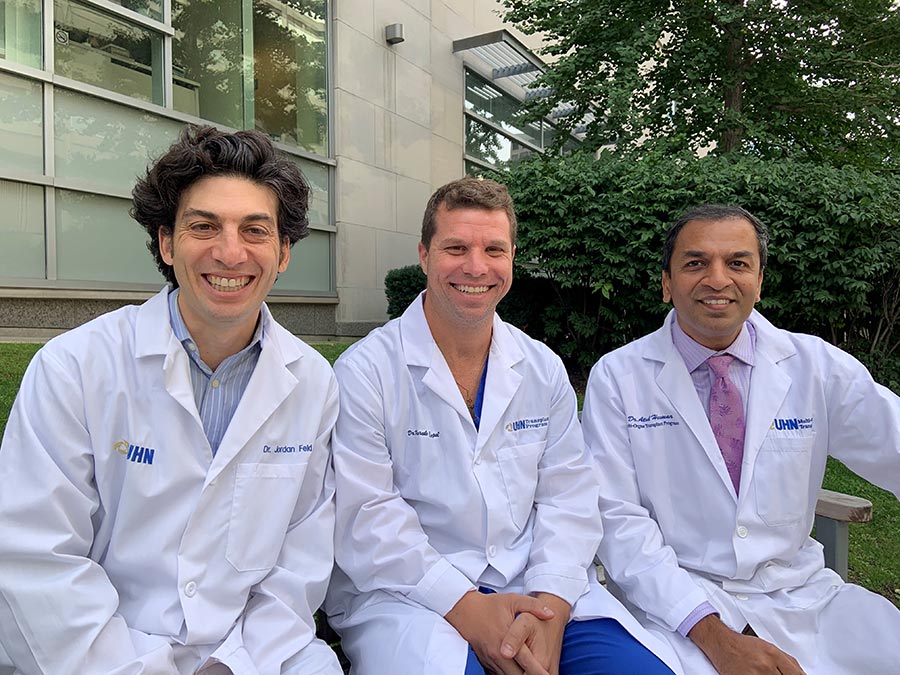

(L to R) Drs. Jordan Feld, Marcelo Cypel and Atul Humar led the clinical trial, which saw 22 patients receive donor lungs infected with the hepatitis C virus. (Photo: UHN)

Two years ago this week, Stanley de Freitas was given hepatitis C infected lungs.

“At that moment there was no choice,” says Stanley. “I either took it or I died, because I was in a desperate fight for my life.”

Ultimately, Stanley was one of 22 patients in a clinical trial who agreed to receive donor lungs infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). The results of that successful trial were published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, one of the most influential medical journals in the world.

The trial was led by Drs. Marcelo Cypel, Jordan Feld and Atul Humar. Read more about the study.

“Our transplant centre is well positioned to do this kind of trial,” says Dr. Humar, Medical Director, Soham & Shaila Ajmera Family Transplant Centre. “We have a unique multidisciplinary team of surgeons, physicians, scientists and engineers working together in an environment where the research talent is closely embedded with the clinical teams.”

A sad convergence of facts led to this ultimately optimistic study.

One of the consequences of the ongoing opioid epidemic is the overdose crisis. Many of the young people who die have been infected with HCV through their use of injection drugs but are otherwise healthy, making them good candidates to be organ donors.

Important step towards understanding how HCV infected organs could help save lives

“The loss of life is a tragedy,” says Dr. Feld, a clinician-scientist and Research Director, Toronto Centre for Liver Disease. “With this program, at least some good can come from such sad beginnings.

“If we used hepatitis C infected organs, we may be able to do a thousand more transplants a year in North America.”

Considering the ongoing challenge of not enough organs and more and more patients in need, this study is an important step towards understanding how HCV infected organs could help save lives.

Half the donor lungs were treated with the Ex Vivo system, whereby the lungs are perfused with a solution, outside the body, a technology pioneered by UHN. The other half of the donor lungs also underwent the Ex Vivo process but with the addition of ultraviolet light, an effective method for sterilization of microorganisms.

Could eventually be applicable to other viruses in donor organs

Remarkably, two of the lung recipients did not get HCV at all and the rest had a markedly less aggressive infection and received successful treatment after transplantation, leading the scientists to believe that the ultraviolet light reduced the infectious capability of the virus.

After six months, 95 per cent of the patients who received the HCV infected lungs were still alive, compared to 94 per cent of those who didn’t receive HCV infected lungs. And with some patients already at the two-year recovery mark, the long-term outcomes are very similar between the two groups.

“Clearly further refinement of the Ex Vivo process is still needed to obtain higher success to achieve complete prevention,” says Dr. Cypel, Surgical Director, Soham & Shaila Ajmera Family Transplant Centre. “However, this was a proof of concept that it is possible.”

This trial was focused on HCV infected lungs but the process could eventually be applicable to other viruses present in donor organs.

In the meantime, Stanley de Freitas recently turned 74.

“I was so weak after the operation,” says Stanley. “But after one week I was walking on a treadmill.

“Isn’t that amazing? Just amazing.”