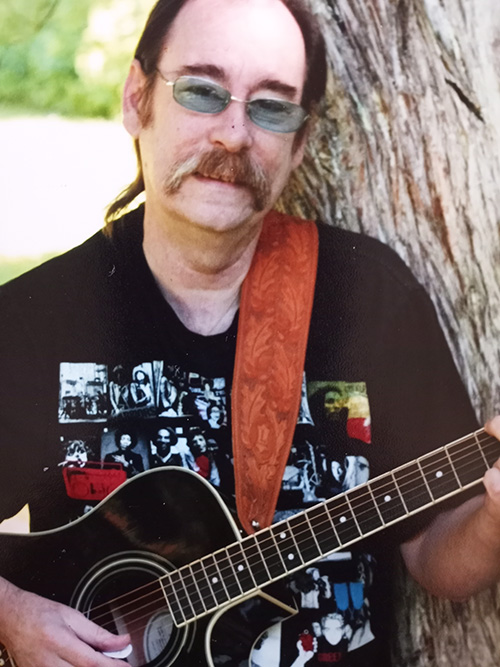

After working with his rehab team to relearn the skills he’d need to play guitar again, Bob Kowalski’s stay at Toronto Rehab ended with him recording a virtual singing and guitar performance for patients and staff. (Video: UHN)

Lucky Man, by Emerson, Lake & Palmer, isn’t just the name of Bob Kowalski’s favourite song to strum to, it’s also how he feels about regaining his ability to play guitar.

It was a goal he set when he first arrived at Toronto Rehab’s Lyndhurst Centre (part of the University Health Network), after a fall down the stairs left him partially paralyzed, and unable to effectively use his lower or upper extremities.

“Before COVID hit, I used to regularly sing and play guitar in bars and restaurants. Entertaining is a big part of my life,” says Bob.

“When I told my care team, they said: ‘Let’s get it done! If you want to play guitar again, tell us what you need.'”

From there, a partnership was formed, where Bob taught his team what it takes to play, and they introduced him to the therapies that would help get him there.

Three months later, Bob has realized his goal, and recorded a virtual singing and guitar performance, to help entertain and motivate other patients.

When patients become partners

At Lyndhurst Centre, multidisciplinary teams support patients with spinal cord injuries in regaining as much functional independence as possible, so they can safely transition back to their communities.

It starts with identifying meaningful rehab goals, says Ani Davtyan, an occupational therapist (OT).

“A lot of important goals relate to a person’s ability to carry out activities of daily living, but when they also represent a piece of who that person is, it makes therapy pleasurable and motivating.”

This often requires care teams to flex their approach to therapy. In order to support Bob’s goals, Ani needed to learn more about the functional movements necessary to play guitar.

“I had never played the guitar, so I asked Bob to be my guide,” Ani says. “Together, we identified what was needed, and divided the activity of playing guitar into smaller goals.

“This allowed Bob to feel like an active member of his rehab team. It wasn’t just me, telling him what to do. It was him, problem-solving around his own limitations, and us coming together as a team, to figure out what he needed.”

For Bob, that meant explaining how far his arms needed to extend, his wrists needed to bend, his shoulders needed to move, and his fingers needed to flex.

“I would describe what skills were necessary, and they would figure out what therapies to prescribe,” recalls Bob.

These therapies included an exercise that required Bob to repeatedly push an object across a table tilted at a 45-degree angle, to help stretch and strengthen arm and shoulder muscles. He also used a hand and finger exercise system, called the Digi-Flex, that fits in a person’s palm, and has buttons that need to be pressed, using individual digits.

“It was very discouraging the first time I tried it, because my little finger, in particular, was so weak,” Bob says. “You may not need a lot of strength in your little finger on a day to day basis, but guitar players do!”

‘No two patients ever have the same goals and the same barriers’

Therapy is never without its challenges, and in Bob’s case, one came in an unexpected form.

“I had forgotten that I’d need to hold a pick, and just assumed I’d grab onto it and start strumming up and down,” recalls Bob.

“But the first time I tried, the pick went flying, because I couldn’t pinch it tight enough between my fingers.”

Seeing this as a creative challenge, Ani got busy adding adhesive Velcro to the tip of the pick, which made it thicker and easier to pinch. The tiny bristles also provided sensory input, which allowed Bob to feel the pick, despite losing some sensation in his fingertips.

“I love being an OT, because my role requires so much creativity,” says Ani.

“Each patient is so unique and no two patients ever have the same goals and the same barriers, so we need to be open to learning from them, to guide our practice, and be creative in our problem-solving.”

When Bob’s therapists asked for 10 reps, he’d give them 11

While setting a meaningful goal is critical to any rehab journey, so is the willingness to do the work.

When Bob’s care team explained that he’d realize the greatest improvements within the first three months of his injury, he was motivated to give it everything he had.

If his therapists asked for 10 reps, he’d give them 11. And the Digi-Flex machine, which challenged him the most, offered the greatest reward, once he made it his constant companion.

“I’d spend hours and hours in my room with that thing, and I really hated it,” he laughs.

“But I wanted to play guitar so badly, I’d do whatever it took.”

Looking ahead, Bob hopes to volunteer one day, as a peer supporter to patients who first arrive at Lyndhurst Centre.

“I want to hold their hand, give them hope, and tell them: ‘It’s your therapists’ job to help you get better, but you can’t just sit there, hoping you’re going to heal. You have to do the work.'”

Therapeutic Recreation puts the ‘fun’ in regaining function

Bob Kowalski may have been surprised to find a music appreciation group on Lyndhurst’s activity schedule, but therapeutic recreation programming and interventions plays an important role in promoting leisure independence in individuals with spinal cord injuries.

“Our goal is to help patients rediscover and develop new leisure pursuits, while providing an opportunity for self expression,” says Marc-Andre Gionet, a wellness partner at Lyndhurst Centre, who co-creates a monthly activity schedule with recreation therapist Charlene Alton, based on current patient needs, interests and therapeutic recreation best practice.

From manipulating bingo dabbers and paint brushes, to throwing bocce balls and horseshoes, most of the therapeutic recreation groups allow patients to practice and develop fine-motor function. Others, like music therapy are all about community and positivity, which help keep patients motivated throughout rehab.

“We like to say that patients are ‘secretly doing therapy,’ because they’re having so much fun, they don’t realize they’re working toward meeting their rehab goals,” says Marc-Andre.

Music appreciation is all about connections, and inviting patients to collectively experience positive emotions.

“This group has allowed patients to develop a sense of belonging and community, which can motivate them through their rehab journey,” he says.