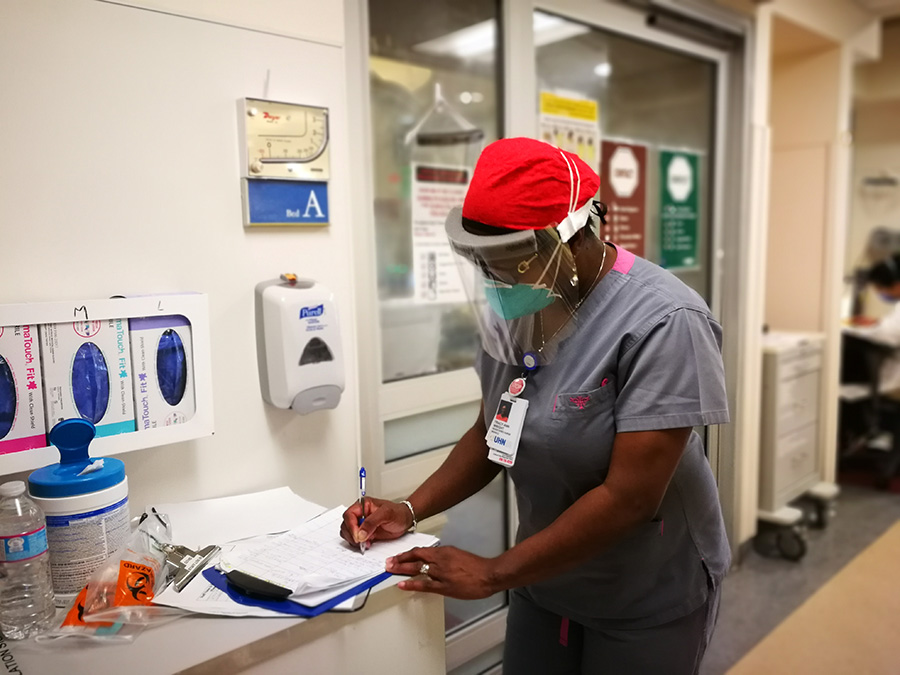

Registered nurse Tracy-Ann Wright in the Medical Surgical/Neuroscience Intensive Care Unit (MSNICU) at Toronto Western Hospital. (Photo: UHN)

They are tools of the trade in critical care – rapidly responding to a patient in distress; consoling a family member at the bedside of a patient who has died; hugging a colleague having a tough day.

But in these days of COVID-19, when wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) is a must, visitors cannot come into hospitals and physical distancing is a priority, UHN staff caring for those most critically ill with coronavirus are adapting the way they work with patients – and with each other.

“It’s changed so much of what we do,” says Denise Morris, Nurse Manager of the Medical Surgical Intensive Care Unit (MSICU) at Toronto General Hospital. “We’re learning to care for patients while limiting our exposure to them, support families when they can’t come in, and reassure each other.

“There’s an uncertainty in this that’s challenging for everyone, no matter their role in the team.”

There’s no playbook for combatting COVID-19. It’s unprecedented among today’s healthcare providers, even those who faced SARS nearly 20 years ago. The sheer volume of cases, the constant change in what’s known about the virus and how best to battle it, and the distressing scenes of hospital staff around the world becoming infected and dying have all fundamentally altered care.

“Obviously, one additional thing that we’re thinking about a lot, is the risk to healthcare workers,” says Dr. Niall Ferguson, UHN’s Head of Critical Care, which includes the MSICU at TGH and the Medical Surgical/Neuroscience Intensive Care Unit (MSNICU) at Toronto Western Hospital. “We’re trying to navigate a course of care that still helps the patient get better and puts our team at minimal risk.

“That’s a factor we normally don’t think about a lot. It’s taken things to a whole other level.”

Members of the team on the Medical Surgical Intensive Care Unit (MSICU) at Toronto General Hospital include: (L to R) social worker Nicole Furey, Nurse Manager Denise Morris, Spiritual Care practitioner Suzanne Robertson and registered nurse Lourdes Calanza. (Photo: UHN)

Extraordinary times calls for extraordinary measures. The ingenuity includes IV poles in hallways connected with long tubing to control drug pumps at the patient’s bedside, reducing the number of trips staff need to make into the room. Spiritual Care practitioners, social workers and nurses using iPads to connect families with patients to share favourite music, emotional final calls, or even prayers after death. Showing support for one another at huddles with spontaneous applause and prayers.

But make no mistake, while these initiatives may reduce exposure, they can carry additional stress.

Registered nurse (RN) Sandra Duntin on the MSNICU says having to put on PPE before going into a patient’s room means needing to dull a reflex action – running to help if something goes wrong.

“You have to take care of yourself by putting everything on, before you can take care of the patient,” Sandra says. “And, one of my biggest fears is that something happens that’s irreversible because I couldn’t get in there quick enough.”

As with so many healthcare workers, anxiety in COVID-19 times is ever-present and comes from many sources. How will we care for a surge in patients who get very sick, very quickly? How long will this go on? Despite all the precautions, can I keep myself safe? Will I infect my partner or my children?

“It’s the fear of the unknown that’s toughest on everyone,” says Rebecca Sinyi, Nurse Manager of MSNICU. “It’s not knowing what our lives and our ICU is going to look like in 10 days, or in 30 days.

“There’s an element of anxiety that comes with COVID-19 that we’ve never faced before.”

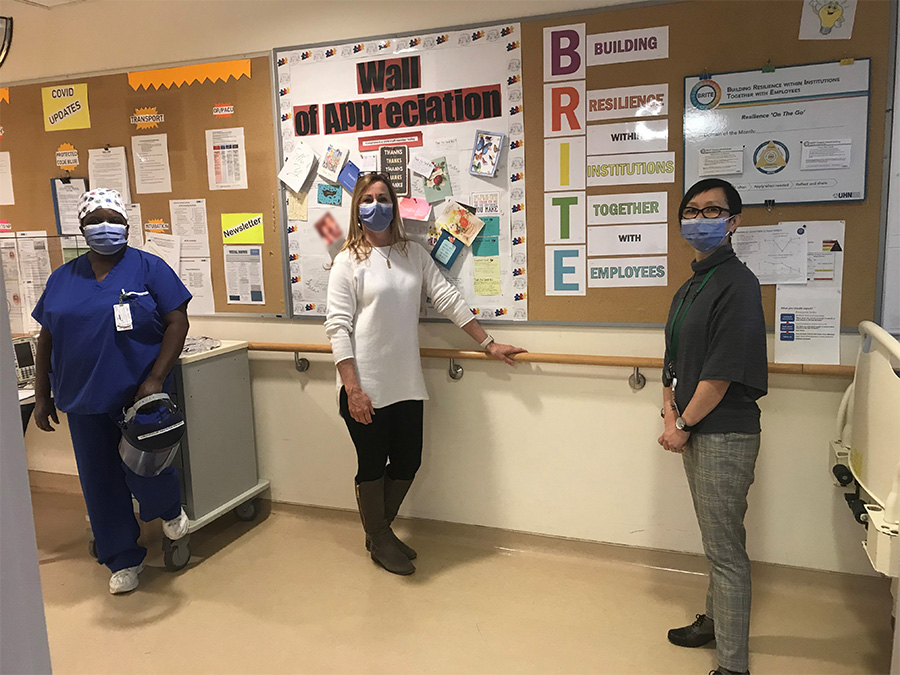

Members of the team on the Medical Surgical/Neuroscience Intensive Care Unit (MSNICU) at Toronto Western Hospital, (L to R) registered nurse Sandra Duntin, Nurse Manager Rebecca Sinyi and social worker Maggie Ho, pose for a photo in front of their Wall of Appreciation and the BRITE practices board, a key part of their daily wellness strategy. (Photo: UHN)

The fact this global pandemic has been playing out for many weeks in the news and on social media only heightens the unease. As the virus has marched across continents and through cities, it has made ill and taken the lives of many healthcare workers and their family members, a fact that is inescapable for people who are working daily with patients who are among the sickest with COVID-19.

“The weight of the decisions we’re making in patient care right now is a little heavier these days,” says Nicole Furey, a social worker on the MSICU. “You can’t help but go home and wonder whether tomorrow, or next week, it could easily be one of us or a family member being cared for.

“Sometimes it’s almost harder not to be here. Because at least when you’re here, you feel you’re doing something, you’re helping and you have some control over things.”

To help staff deal with that anxiety, both Rebecca and Denise have fielded phone calls at all hours to hear the concerns of team members. Extra safety huddles have been implemented, including sessions to address questions about PPE and the virus, exchange the latest information on caseloads at UHN and across the region, and any changes in procedures.

Lavender alerts – sessions facilitated by a Spiritual Care member that offer a safe, confidential space for to talk about their experiences of moral distress, emotional fatigue, stress after Codes and traumatic deaths – are happening more frequently. Some team members also decorate their masks with sparkles and jewels, others joke that they always tell their colleagues they’re smiling at them even though their mouths are always covered.

“We are a very creative group, with a very creative leader,” says Suzanne Robertson, Spiritual Care practitioner on MSICU. “And, we’re really good at what we do.

“We know how to care for people and we just need to adapt to the situation to continue doing it.”

Ingenuity being used on the units to limit the exposure of staff to COVID-19 positive patients includes these IV pumps outside the room which have Wifi monitoring for machines. (Photo: UHN)

In addition to the clinical load of COVID-19 admissions on both UHN critical care units, TGH’s MSICU is the regional centre for those patients who need extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machines, which is a treatment used for those who are among the sickest.

The units have also become key focal points of research on how to treat COVID-19 patients, including clinical drug trials and mechanical ventilation. They’re also serving as a classroom of sorts, offering a great learning experience for medical trainees, as well as a place to develop training tools in case a surge of coronavirus patients requires non-critical care medical personnel to work in the ICUs.

The pandemic response has not only led to ingenuity, it’s also strengthened bonds on the already close-knit teams. And, that spirit of cooperation extends beyond the walls of each unit – Denise thanks colleagues in the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre’s Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit (CVICU) and Coronary Intensive Care Unit (CICU) for taking non-coronavirus critical care patients so the MSICU can focus on those with COVID-19; and Rebecca offers a shoutout to Dr. Alon Vaisman from Infection Prevention & Control (IPAC) for coming to MSNICU huddles to answer staff questions about the virus.

“We’ve always helped each other, but we’re even more gung-ho now because we realize no matter how good you are at what you do, you cannot do it alone, you need the team’s help,” says Sandra at MSNICU. “We’ve got each other’s back even more now.”

That teamwork manifests itself in numerous ways – helping colleagues put on and take off PPE properly; perfusionists and other allied health professionals rigging workarounds that help limit risk of infection to staff; ensuring teammates are finding a work-life balance despite being on the frontline.

But one of the biggest needs is emotional support for patients, who are unable to have visitors.

“It’s really sad,” says Lourdes Calanza, an RN on the MSICU at TGH. “When families are here, there’s a link, we offer each other support and if they don’t make it, we can share grief with them.”

Dr. Martin Ma on the MSICU at TGH after a successful intubation. (Photo:UHN)

Maggie Ho is a social worker on the MSNICU at TWH, which because of the neuroscience component has a higher percentage of non-COVID-19 patients than the MSICU at TGH. She says with no visitors allowed, it’s easy for patients to get depressed, which means it’s even more important for her to engage them.

Families are typically “very comforted and grateful” when they learn that they can make an electronic connection and feel closer to their loved one despite being unable to come in, Maggie says. But that gratitude goes both ways, she says.

“It’s strange but at the same time I feel privileged,” Maggie says of helping a family FaceTime with a patient who they cannot visit. “It’s a very intimate moment, a very private moment.

“It’s important that we be creative and allow that special time for the family,” noting that under normal circumstances such conversations would often happen in the absence of the care team.”

In the UHN critical care departments, just like everywhere else, no one knows how the pandemic will play out. But amid all the anxiety – for patients, families and themselves – staff remain resolute.

“I wake up in the morning and in the face of uncertainty I feel I’m ready to take on the day because I know my team will be there for me,” says Lourdes on the MSICU at TGH.

“Despite all the challenges we face, I feel like we can get through it together.”