Emmanuel Boakye knows how serious a sickle cell crisis can be. He nearly died from one.

At 28, he was suddenly struck by an excruciating pain in his chest. He lost his ability to walk before falling into a coma.

Three weeks later, Emmanuel woke up in Toronto General’s ICU, where the care team saved his life.

“I couldn’t even recognize myself,” he says. “I lost all my hair. I lost 50 pounds. I looked 30 years older.”

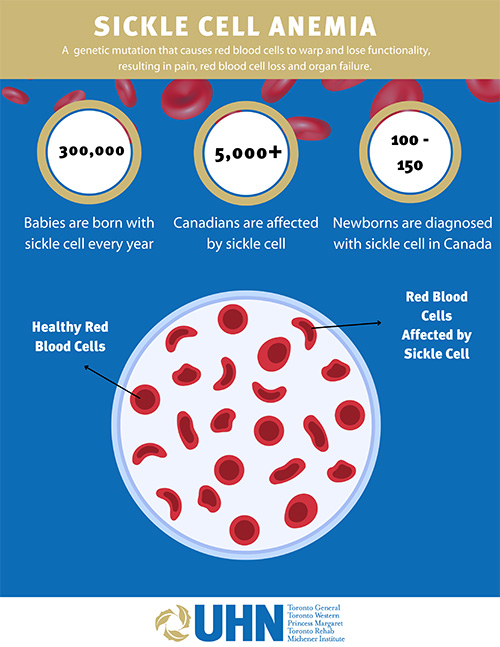

Now 33, Emmanuel knows he was lucky. Sickle cell anemia is a genetic mutation that disproportionately affects Black communities. During a crisis, red blood cells physically morph into a sickle shape, not only causing extreme pain, but internal damage as they circulate throughout the body.

While it’s one of the most commonly inherited conditions in the world, it’s not taught in-depth in nursing or medical school, which makes it difficult for hospitals to manage patients when they arrive.

“A lot of hospitals aren’t as educated about sickle cell,” he says, emphasizing that the difference in care could have been a matter of life or death for him.

But now, Emmanuel wants others to know there’s new hope for sickle cell patients.

As part of UHN’s commitment to health equity, the Blood Disorders Program recently hired Karen Fleming, a clinical nurse specialist dedicated to improving care for sickle cell patients in Black communities.

“You can’t talk about sickle cell disease without referring to the racial biases and inequities that impact access to care and patient outcomes,” says Fleming, a life-long sickle cell advocate who joined the Red Blood Cell Disorders Clinic at UHN earlier this year.

Sickle cell disease is a genetic mutation that originated in Africa and the Indian subcontinent as an immune response to malaria. It occurs when a child receives one sickle cell gene from each parent, making it an inherited condition that predominately affects people of African descent.

Karen says the lack of medical professionals trained to treat sickle cell has reinforced discriminatory structures in health care that can put Black patients’ lives at risk. Being stereotyped as drug-seekers, delays in receiving treatment and inadequate discharge and follow-up are some of the ways systemic biases can affect patient care.

“Not only are they navigating the system with an already complex, misunderstood condition – they’re also navigating it as Black patients,” Karen says.

Karen aims to address these barriers by collaborating in the education of Emergency Department (ED) staff about sickle cell disease and how to manage a crisis, while reducing racialized experiences for patients. She says this will ultimately increase the sense of urgency when sickle cell patients arrive there.

“Staff know it’s serious if someone is experiencing a heart attack, so why not a sickle cell crisis?” she says.

Much like a heart attack, the longer it takes for a sickle cell patient to receive care, the more pain they endure. Treatment delays can also contribute to the organ and bone damage sickle cell patients experience, which can impact their life expectancy.

The highest mortality rates are between the ages of 18 and 35.

Dr. Kevin Kuo, a sickle cell researcher at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, says sickle cell patients in Black communities face a triple disadvantage.

“They live with a chronic disease that affects quality of life and life potential, often limiting upward socio-economic mobility,” Dr. Kuo explains. “Then there is the scarcity of research addressing issues of great importance to Black populations, on top of the negative bias frequently encountered during health care interactions.”

For example, sickle cell patients often report that ED staff don’t realize how much pain a crisis can cause. The lack of awareness about sickle cell combined with delays in administering opioids has created a care gap for patients that not only prolongs their suffering, but leaves them feeling stereotyped as drug-seekers, Dr. Kuo says.

This is why 60 per cent of sickle cell patients delay going to the hospital when in a pain crisis – they’re trying to avoid a negative health care experience from happening again, he says.

Though Emmanuel arrived at the ICU in 2019 in time to save his life, the crisis did have a lasting physical impact. He had a stroke and was diagnosed with total organ failure. During his coma, he needed emergency surgery to repair the damage the sickle cells caused to his kidneys, lungs and intestines.

Emmanuel was also diagnosed with avascular necrosis – death of the femur and hip bone – an incurable condition that only a hip replacement can mend, caused by the lack of red blood cells reaching his bones.

Emmanuel continues to struggle walking.

“Growing up, I never thought it could get this bad,” he says. “No one ever told me this condition would eventually cause life-long damage, or worse.”

But then, after his most devastating crisis, Emmauel made a groundbreaking discovery. His sister was a blood type match and was able to participate in an allogenic stem cell transplant at the Princess Margaret – a procedure that can potentially cure sickle cell anemia by removing diseased blood and replacing it with healthy cells from a donor.

The Princess Margaret was one of the first hospitals in Canada to offer a cure for adults living with sickle cell disease, and Emmanuel was the fifth patient to participate in the program. So far, the program has administered seven stem cell transplants for adults with sickle cell.

Emmanuel encourages patients to speak to their family doctors about their options.

“You never used to hear sickle cell and cure in the same sentence, but times have changed,” he says.

With the likes of Karen, Dr. Kuo and other members of UHN’s Blood Disorders Program championing the fight against this complicated disease, Emmanuel has never felt more hopeful.

“If there’s anything I want sickle cell patients to know, it’s that you’re not in this alone,” he says.

“There are people out there that are rooting for you.”