UHN emergency physician Dr. Andrea Somers wouldn’t call herself a hero. For her, standing by your core values as a medical professional and facing whatever challenge comes your way is just something that healthcare workers do.

“I can’t think of one instance where people have run the other way. Emergency doctors typically run into the fire, not away from it,” says Dr. Somers.

So, in March 2020, when COVID-19 arrived, it wasn’t a question of if, but of how, Dr. Somers and her team should fight COVID-19. “I can’t think of anyone who said, ‘I’m not doing this,’” says Dr. Somers.

When COVID-19 first hit, it was unclear how the virus spread, what the best way to fight it was and how Dr. Somers and her team were going to protect themselves while helping others. “That was the scary part. You had questions about coming back home,” Dr. Somers recalls. “Are you safe to be around your husband and kids?”

It was a common thought among healthcare workers: can I even go back to my family after a shift? Dr. Somers recalls talking to a friend to find temporary housing that she could stay at alone to protect her two sons and husband. “I think it crossed all of our minds at various points,” she says.

No emergency healthcare worker knows what to expect during a shift, but COVID-19 has provided Dr. Somers with some certainties: when she arrives at the hospital, she’ll grab her face mask and face shield, and then change out of her street clothes and into her scrubs to go meet the resident who will be working with her for the day. Every time she sees a new patient, or enters a new room, she has to change out of her old gown and gloves into a fresh set. The mask and face shield never come off. During one shift alone, she washes her hands 40 to 50 times.

“There’s going to be a whole new rigour to our hygiene routines,” says Dr. Somers.

Because of these new COVID-19 protocols, she’s not able to bring a chart into a patient room with her. Instead, after she assesses each of her patients, she’ll go back to her desk and record all their information. It’s a time-consuming process for a time-sensitive job.

Of course, this is not unique to Dr. Somers. COVID-19 has necessitated hygiene rituals be taken up a notch for all. Post-shift, any item that was being carried during a shift now has to be wiped down or left at the hospital altogether. If you want to stop and eat on shift, you have to make sure there is adequate space in the break room because it’s not safe to take your mask off and eat with other people.

For people who are used to running from code blues to intubations to checking multiple test results for different patients, these extra steps add up. Luckily, healthcare workers aren’t scared of hard work. Dr. Somers got into medicine for that exact reason. She loves the challenge of solving problems, of being able to make an intervention that will either fix a problem, avert a disaster or make an immediate impact on a patient’s outcome.

It’s part of her job, and while she’ll do it without hesitation, that doesn’t remove her from the stresses of working on the front lines of the pandemic. She stresses that doctors are, at the end of the day, humans like the rest of us. This past December, Dr. Somers’ father passed away, in the same hospital she still works at every day. Last summer, her kids were turned away from playdates because people were scared that their mom was working in a hospital with COVID-19.

“We’re also just people. We’re still coming home to kids who are being homeschooled,” says Dr. Somers. “This impacts us all and we’re going through it with you.”

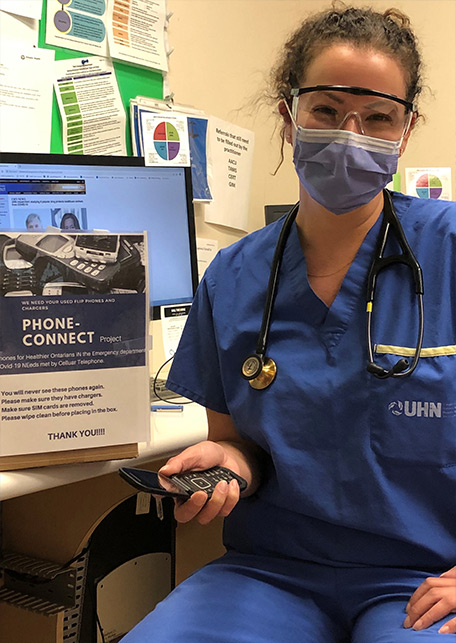

And while all healthcare workers have adapted to the challenges of COVID-19, they haven’t let it slow them down. Dr. Somers notes that it has been an inspiring time for many of her colleagues. “Just the degree of scholarly output has been huge and the degree of clinician engagement in non-patient-facing activities has been really massive,” says Dr. Somers, who started the PHONE CONNECT program, which places digital equity at the centre of care. The program distributes cellphones to vulnerable populations to stay connected to resources.

Healthcare workers’ ability to show compassion and provide care while dealing with danger is a remarkable feat. But Dr. Somers stresses that this ability to make a difference, to help people, isn’t exclusive to healthcare workers. She says we all have a part to play in ending the pandemic.

With the vaccine here and spring arriving, Dr. Somers is hopeful. Until then, Dr. Somers and her team will continue to do what they know best: solve problems and save lives.