Dr. Jordan Feld, Research Director at UHN’s Francis Family Liver Clinic, led an international medical trial in 2015 that made the breakthrough discovery of a pill that cures hepatitis C. A decade on, the disease remains a major killer in Canada.

To mark World Hepatitis Day 2025 on July 28, Dr. Feld discusses a wide range of issues, including the different types of hepatitis infections and how they are acquired, the need for more screening of people for hepatitis B and C, and work being done at UHN to advance research and culturally safe care.

How significant a health threat is hepatitis in Canada? Globally? Who is most at risk?

Viral hepatitis continues to be an enormous global public health problem and a major killer in Canada. About one million people die every year from hepatitis B and C infections around the world. If current trends continue, viral hepatitis will cause more deaths annually than the “Big 3” global public health threats — HIV, tuberculosis and malaria — combined. And, this is not just a problem elsewhere — hepatitis C causes more years of life lost in Ontario than any other infectious disease; hepatitis B is fourth on that list.

Hepatitis C is spread by blood-to-blood contact. In Canada, most new infections are acquired through injection drug use, and many newcomers to Canada come from places where hepatitis is more common, where infection can happen through contact with unsafe medical equipment. Hepatitis B is spread from mother to child, sexually and through blood-to-blood contact. Around the world, most people with chronic hepatitis B acquired the infection early in life — from unsafe medical practices or through pregnancy or other household transmission.

Hepatitis B and C cause very few or no symptoms until liver disease is very advanced, so people can be living with these infections for years or decades without knowing they are infected.

What would you share to debunk some of the common myths about hepatitis?

People often confuse the different hepatitis viruses. They are actually quite different. Hepatitis A is spread through contaminated food and water, and although you get sick from hepatitis A, it does not lead to the long-term complications of liver cirrhosis and liver cancer that occur with hepatitis B and C. This can be confusing because people think you can get hepatitis B and C — the more serious ones — from casual contact or sharing things such as water bottles — this is not the case but can be very stigmatizing and isolating for people living with chronic hepatitis B or C infections.

There are effective vaccines for hepatitis A and B, but there is no vaccine for hepatitis C. We are working on trying to develop a vaccine for C but fortunately, we have very effective treatment that can cure almost everyone who is diagnosed.

Newcomers often think they have been tested for hepatitis infections at the time of immigration to Canada. This is rarely the case. Testing is not required for immigration, and we often see very delayed diagnoses in those populations.

What are the biggest challenges in diagnosing hepatitis today?

The biggest challenge is getting people to get tested! Most people have few or no symptoms until they have very advanced liver disease, so we cannot wait for people to feel unwell to seek out a test. Testing is easy — just a simple blood test — but it needs to be requested specifically. Unfortunately, Canada still recommends testing people based on their risk factors. Although this might sound like it makes sense, it doesn’t work, and leads to a lot of people with very late diagnoses.

The United States and other countries recommend screening the entire adult population for hepatitis B and C. Canada should be doing the same. Population screening is cost-effective because we can cure people with C and treat those with B, preventing serious complications and preventing unintentional transmission to others.

Population screening is also easier to implement — just like getting your blood pressure or cholesterol checked, people should be screened for hepatitis B and C. That is a lot easier to implement than trying to figure out if someone has a risk factor. Risk-based testing is also very stigmatizing by associating the test with the risk factor. Health care providers often don’t ask about “risk factors” and rely on stereotypes of who “appears” at risk to make their decision, and people may not remember something from years ago even if they are asked — the end result is people don’t get tested.

What does screening and treatment for hepatitis typically look like — and how has it changed over the past decade?

The progress in the past decade has been truly remarkable. Treatment for hepatitis C used to be miserable — up to a year of weekly injections with lots of side effects and a very low cure rate. Now, we can cure almost everyone — more than 95 per cent with eight to 12 weeks of one to three pills per day with almost no side effects. It’s been an amazing change. The treatment is now so effective that the World Health Organization (WHO) is calling for the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030. Canada has committed to meeting this target.

For hepatitis B, we have a fantastic vaccine that is protective, and our treatments are very helpful, but not curative. There is a lot of work ongoing to develop new curative treatments, which is something UHN is very involved in. In the meantime, we need to improve our vaccine policy, specifically we should be vaccinating all newborns for hepatitis B as the WHO recommends. We should also be doing a better job of ensuring people are diagnosed and getting treatment if they need it.

How is UHN helping to end the stigma associated with hepatitis?

UHN is leading efforts in Ontario to achieve hepatitis elimination targets. We have formed the Viral Hepatitis Care Network (VIRCAN) which focuses on partnering with community organizations to improve hepatitis screening and treatment, as well as leading research efforts to improve the quality of hepatitis care. We spend a lot of time working with some of the most marginalized populations, particularly people who inject drugs, people experiencing homelessness, incarcerated individuals, newcomers, Indigenous Peoples, gay and bisexual men who have sex with men, and other vulnerable communities. We work with community organizations and prioritize involving people with lived and living experience to ensure that we deliver care and promote screening as part of holistic, wraparound, non-stigmatizing care.

What action does UHN take to ensure hepatitis care is culturally safe and accessible for diverse communities?

Our VIRCAN team works closely with community organizations that serve specific populations to provide them with expertise in hepatitis screening and care. We have specific programs to work on liver wellness in Indigenous communities, particularly First Nations communities around the province.

We care for a large population of people living with chronic hepatitis B who come from every corner of the globe. We work closely with CATIE and other community organizations to promote linguistically and culturally appropriate education programs as well as doing specific outreach programs to newcomer populations from regions where hepatitis B is common. Working closely with community leaders, we always try to ensure that screening and linkage to care are done in partnership with communities in the ways that work best for the members of the community.

What is UHN doing to help achieve the WHO targets reducing new infections and deaths?

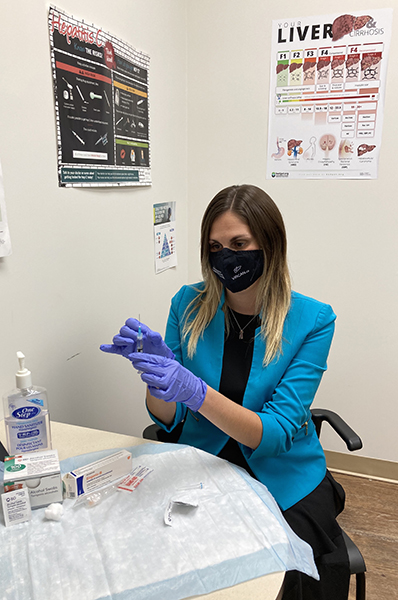

We have a very active role in many aspects of viral hepatitis elimination efforts in Ontario and across the country. In partnership with CATIE, our VIRCAN team oversees the Roadmap for HCV Elimination in Ontario that is the guiding strategy for HCV elimination efforts in the province. Bernadette Lettner — a nurse with extensive frontline experience treating hepatitis C — is leading that within our team. She works closely with Camelia Capraru, the Executive Director of VIRCAN, and Dr. Mia Biondi, a phenomenal scientist and nurse practitioner with extensive experience in viral hepatitis care — but it is a huge team effort with the entire VIRCAN team and our partners playing critical roles. The efforts have involved working with the Ministry of the Solicitor General to implement hepatitis testing and treatment in prisons, expanding and simplifying diagnostics, including leading the first provincially funded program in Canada for point-of-care hepatitis C antibody testing, and working closely with Indigenous communities around the province to develop strategies for promoting liver wellness in Indigenous populations.

For hepatitis B, we have been advocating to implement birth dose hepatitis B vaccination in Ontario, and ideally across the country, and we are working with newcomer populations to advance screening for hepatitis B and hepatitis D, a liver infection caused by hepatitis D virus but only seen in those who already have hepatitis B, to ensure people are diagnosed and linked to care and treatment.

What’s on the horizon for hepatitis research and treatment? Are there any promising developments or innovations at UHN that give you hope?

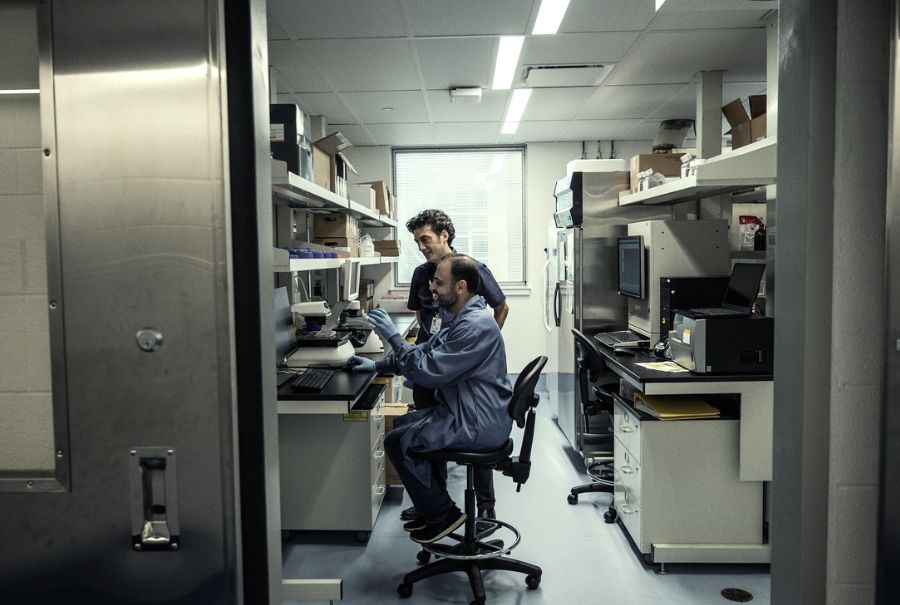

There’s a lot of exciting work happening at UHN. There is a lot of promise in new therapies being developed for hepatitis B and our team is leading innovative trials both in the clinic and the lab. We are doing cutting edge science with many of the newest single cell technologies to better understand disease pathogenesis and mechanisms of action of new treatments to help advance to curative therapy. There’s cautious optimism that within the coming years we will have curative treatment for hepatitis B, and by extension D, that will enable us to readily limit the enormous burden of disease caused by these viruses.

For hepatitis C, in addition to our efforts to expand treatment and improve models of care for marginalized populations, we are actively working on vaccine development. Despite our effective treatments, new infections continue to keep pace with cures, meaning that we will really need a vaccine to truly reach elimination.

Developing a vaccine for hepatitis C is very challenging. It is an incredibly diverse virus and we do not have experimental models to test promising vaccine candidates. As a result, now that we have such effective treatment, we are leading a global effort to develop a Controlled Human Infection Model (CHIM), in which we will intentionally infect people with hepatitis C to accelerate vaccine development. Of course, we will treat them if the vaccines are not effective. We have Canadian Institutes of Health Research and other funding for this project and will hopefully be starting our first infections very soon. Excitingly, one of the more promising vaccine candidates to be tested in the CHIM approach will be a vaccine developed at UHN.

No one ever changed the world on their own but when the bright minds at UHN work together with donors we can redefine the world of health care together.