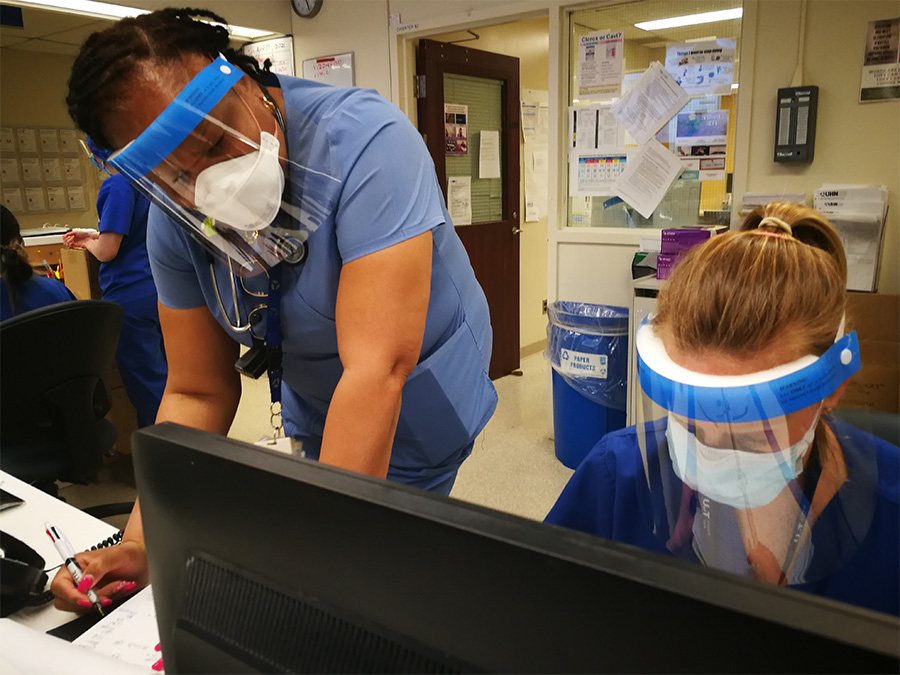

Dr. Kali Barrett, a Critical Care physician at Toronto Western Hospital, has been an outspoken advocate for patients during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Photo: UHN)

Dr. Kali Barrett stands outside a patient room donning protective armor to shield against the COVID-19 virus. The movements of the Toronto Western Hospital (TWH) Critical Care physician are practiced and deliberate. It starts with the long-sleeved neck-to-toe canary yellow gown. Cotton ties around back at the waist and neck. The N95 mask, followed by a clear plastic shield to cover her face, and finally the thin blue gloves.

As Dr. Barrett completes her PPE ritual on this morning, 22 of the 34 patients in the hospital’s Intensive ICU are severely ill with COVID-19. The total patients exceed TWH’s ICU typical capacity. In normal times, those patients would be managed by two care teams. To accommodate the pandemic-induced surge of patients the hospital has stretched – both in terms of manpower and space. A third care team was first created back in January during the peak of Wave Two, and then re-constituted when Wave Three got underway. As for space, eight beds in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) were freed up when scheduled surgeries were shut down.

For today’s shift, Dr. Barrett is covering the ICU patients in PACU, the Critical Care Response Team (CCRT), and new consults from the Emergency Department (ED). First up is an elderly patient admitted due to respiratory issues and weakness to the point they were having difficulty getting out of bed and walking.

Dr. Barrett is pleased to see she’s teamed up with CCRT registered nurse Dorrette Ruddock, who has decades of experience. She has been at TWH since 1988, when she started out as a blood tech. Mrs. Ruddock is also a veteran of the 2003 SARS outbreaks in Toronto where the majority of cases were healthcare workers, patients, and hospital visitors.

“The nurses and our teams who worked through SARS who have that lived experience, like Dorrette, there is this calm about them – like, ‘we’ve seen this before. We’ll be able to get through it,” says Dr. Barrett. “And, I have found so much strength from their experience and their reassurance because we know it will end.”

Together, Dr. Barrett and Mrs. Ruddock examine the elderly patient with breathing issues and weakness, then find a quiet area off the nursing station to plan next steps.

“The cough is not great, and their voice is not strong,” says Dr. Barrett. A call is placed to neurology. The respiratory therapist (RT) is paged. They speak to the resident and fellow with responsibility for the patient. After consultation, it’s decided the patient be moved to a neurology bed where her condition and breathing can be monitored more closely.

Dr. Barrett heads down to the ED where an elderly patient has arrived with cold-like symptoms, a crackling sound when they breathe, and pain in the back. X-rays reveal one lung is white, indicating it is filled with fluid. Could be pneumonia. Or worse, a mass. Dr. Barrett orders more tests including CT imaging of the lung.

While awaiting those diagnostics, it’s on to the makeshift ICU in PACU where Dr. Barrett examines two intubated patients. One is a recovered COVID-19 patient whose lungs are shot. The second suffered brain damage after a drug overdose. At the foot of each bed, sits a portable workstation for the nurse assigned to monitor these critically ill patients one-on-one. Although, Dr. Barrett says, that level of care has been dented by the pandemic.

“Yesterday we had one nurse care for both of these patients, so she was caring for two intubated and sedated patients by herself and that’s typically not how we care for those types of patients,” says Dr. Barrett.

Adapting patient care to the unpredictability of the pandemic is a new experience for Dr. Barrett and her colleagues. Staffing demands, especially in nursing, sometimes exceed available personnel. Then, there is the issue of not having patient families present. And the online goodbyes.

The fallout of this has a name – moral distress.

“There’s the moral distress from the continuous exposure to these patients that don’t do well.

And the vicarious trauma of having these really hard conversations over FaceTime and iPads, that certainly destroys your humanity and your emotion,” says Dr. Barrett.

After examining the two intubated patients, Dr. Barrett sits at the end of their beds to write detailed notes. The patient with brain damage is not likely to recover. She needs to call the family to discuss a plan of care. Breaking this news will have to be over the phone.

Dr. Barrett is searching the Nursing Station for a quiet area to make the call. Her cell phone vibrates.

Her husband has sent her a video. A slickly-edited production starring their three children – aged five, three and 10 months. The made-for-mommy movie has a dramatic plot set in a “haunted hospital” – inspired by her recent overnight shift when her on-call room was located in a spooky “abandoned” wing of the hospital. The 10-month-old is content with her part of simply sitting in the middle of the bedroom and staring at the camera whenever it lands on her. The other two run around battling the imaginary demons. To save the hospital Dr. Barrett’s eldest recommends they call in the “Ghostbusters” to save the day. This is precious stuff. For the whole three minutes, she cannot stop smiling.

Dr. Barrett puts down her cellphone, and picks up a landline to call the mom of the patient who suffered brain damage. In a compassionate mother-to-mother conversation, Dr. Barrett explains the situation. Your child has no awareness of surroundings. There is no perception. The eyes do not track when opened. The trajectory is unlikely to change. The notion of meaningful recovery is gone. The mom asks for 24 hours to decide what to do. Dr. Barrett tells her how sorry she is. They will talk again tomorrow.

“To be having those kinds of conversations over the phone, you really feel like you’re short changing the family members,” explains Dr. Barrett, “There’s a greater drive to do even more and do a good job and try to be there as much as you can.

“Within my own family this pandemic has really made us all really appreciate each other. We have family friends who died from COVID-19 so it reminds us that every day is precious and that really what matters is those really simple times with your loved ones at home.”

After a bag lunch at her desk to catch up on emails and her work as Assistant Scientific Director of the Ontario Science Advisory Table Secretariat, Dr. Barrett is again on the move. She swings by the COVID area of the ICU to consult with a nurse about a patient’s condition and medications. Next, it’s up to the 6th floor Fell Pavilion where a patient recovering from surgery is not responsive. Upon examination, Dr. Barrett suspects the patient is drowsy from opioid painkillers and prescribes Narcan to reverse the effects. Within minutes, the patient is alert and responsive.

By-mid-afternoon, the CT scans and assessment have come back for the 90-year-old patient in the ED. There is a mass on the lung. Likely cancer. More tests are needed to plot next steps and treatment options. This will be another tough conversation.

Late in the afternoon, it’s back to the office and emails related to her work with the COVID-19 Modelling Collaborative – a team led by UHN scientist Dr. Beate Sander – which has contributed to the province’s modelling, projecting the number of new cases of COVID-19 and the numbers admitted to hospital and ICUs.

“We produced modelled projections of hospital and ICU occupancy for patients with COVID-19,” Dr. Barrett says. “The findings were shared with decision-makers, and then presented publicly by Dr. Adalsteinn Brown. The next day, the Premier enacted new public health measures to help reduce transmission and would refer to our modelling. Then, we would see the number of new cases drop and the curves bend. I can’t describe it, as a physician, I probably did more good contributing to that modeling than all the individual patients I’ve seen in my career. And so it’s been an unbelievable experience for me.”

That was the experience for the first two waves of the pandemic. In the lead up to Wave Three, modelling did not appear to have the same cause and effect. And it was not for lack of issuing their projections.

“In February, it was clear that the B117 variant was here and we looked at what had happened in other jurisdictions, particularly in the U.K. and London, where if you didn’t get your reproductive number below 0.7 the variant was going to take off and you were going to have this sort of massively exponential growth,” explains Dr. Barrett, “And instead of actions to control growth of the variant, the response was gradual reopening and it was just, you knew exactly what was going to happen… the numbers of patients with COVID-19 in ICU are going to go up.”

And they did. Way up. By the end of April, there were over 880 people in critical care beds because of COVID-19. A pandemic first.

This prompted Dr. Barrett to take a more vocal public stance advocating for patients. She co-authored a letter signed by over 150 critical care physicians urging the provincial government to impose tighter restrictions. And she appeared on TV news programs to air her concerns about the pandemic’s impact on Ontario’s hospital system.

It’s clear Dr. Barrett’s voice resonated. A CBC TV interview has over 1.3 million views and counting.

“When I was seeing the patients in ICU who had COVID who’d been transferred in from Brampton – every single one of them had a workplace exposure, and/or their partner had had a workplace exposure and then everyone in their house got sick,” says Dr. Barrett, “And the policies have not done anything to protect those people…the people that keep our city and our society running but don’t have benefits, sick pay, unions – the supports that they need in order to keep themselves safe…and so that’s just been really awful to see.”

Dr. Barrett was reticent to voice her concerns at first, but was emboldened by comments from UHN President & CEO, Dr. Kevin Smith on Twitter.

“I noticed Kevin Smith was being vocal and critical of policy, and I felt if Kevin Smith feels comfortable doing that, and basically what I’m saying is concordant with what he’s advocating for… I felt why not, I’m going to speak out and be on the right side of history on this one.”