Just as an out-of-control infection was about to cost Madison Freeman her eye, the ophthalmology team at University Health Network stepped in to save it. (Photo: Tim Fraser)

By Glynis Ratcliffe

When 27-year-old Madison Freeman left for Central America in February 2022, her plan was to travel from country to country, teaching English to schoolchildren. The trip was the opportunity of a lifetime, but it quickly became a living nightmare in which Freeman nearly lost her right eye because of a fast-moving corneal infection called fungal keratitis that she acquired in Honduras.

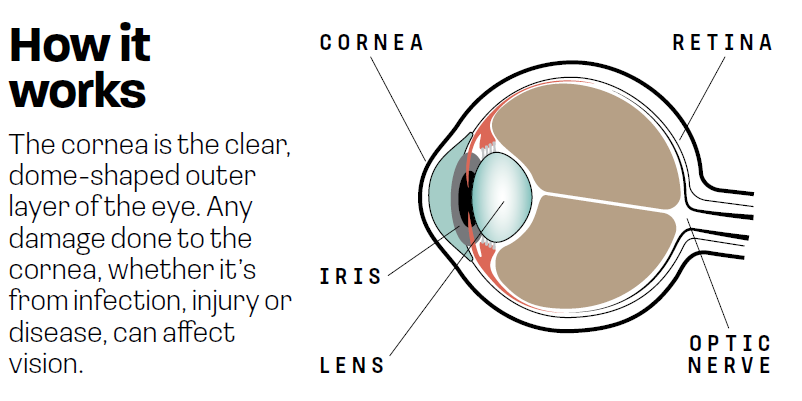

Often referred to as the window of the eye, the cornea is the transparent, dome-shaped covering over the iris and pupil, made up of six layers and measuring just a half-millimetre thick. In Freeman’s case, her fungal keratitis was caused by a fusarium species, a fungus that lives in tropical and subtropical soil in countries in Africa, Asia, and North and South America. Symptoms include redness, pain, excessive tearing, discharge and sensitivity to light.

About one million people are diagnosed with fungal keratitis annually worldwide. Of those cases, approximately 100,000 need the infected eye removed, either because of late diagnosis or a poor response to treatment.

Thankfully, Freeman’s eye was saved with a cornea transplant performed by Dr. Clara Chan, cornea surgeon, and Dr. Sara AlShaker, cornea surgery fellow, both with the Sprott Department of Surgery and the Donald K. Johnson Eye Institute at University Health Network (UHN). But her journey to that UHN operating room (OR) was a harrowing one.

A foreign infection in a foreign land

Freeman was staying in a small village when she felt sharp pains in her right eye in early May. A local physician diagnosed her with conjunctivitis, but as the pain worsened over the next two days and she sought out a second opinion, her situation escalated. She was sent to a hospital, where she needed emergency surgery.

As Freeman lay on an operating table with a clamp keeping her right eye open, she tried desperately not to move. The surgeon had just explained that her cornea was so inflamed that what he was about to do would likely hurt, despite freezing. A medical team held her down as the surgeon began to cut the infection out of her eye, while the staccato of unrecognizable Spanish words coming out of their mouths only left her terrified. “It was horrifying; one of the most painful things I’ve ever experienced,” Freeman says.

A few days later, the surgeon could see the infection had spread. She was whisked into an OR for a second surgery. This time, they took some of the conjunctiva – the outer layer that covers the white of the eye – and sewed it together overtop the cornea to encourage the eye to heal itself. That resulted in temporary blindness in that eye. “While he was suturing the tissue closed, I could see less and less until it was nothing,” she says.

Soon after the second surgery, on Victoria Day weekend, Freeman and her partner returned to Canada in case further treatment was needed. Her surgeon said he had done all he could.

Unexpected escalation

The way Freeman was treated in Honduras is not typical in Canada. Here, she would have received antifungal eye drops, with surgery used if the infection didn’t improve. Lower-resource countries often don’t have cornea tissue readily available, making it impossible to perform an emergency transplant.

The pain sent Freeman, now in Canada, to her local emergency department in Waterloo, Ont., where two cornea specialists told her to prepare for the possibility of losing her eye. She knew the infection was serious, but she was still shocked.

“I didn’t know that was even on the table,” she recalls. “I felt very low, and as much as you want to be positive, the idea of not having an eye anymore is frightening.”

Fortunately, Freeman’s mom, who had flown in from Alberta to provide moral support, wasn’t ready to accept her daughter’s eye removal as a foregone conclusion. Together, they pushed for a second opinion, which resulted in a referral to Dr. Chan and her team at UHN.

In good hands

When she met Drs. Chan and AlShaker, Freeman felt relief. The room filled with other residents and specialists, all examining her eye – which was still sutured shut – and discussing the details of her case. She remembers Dr. Chan and others on her team telling her they were going to do whatever they could to save her eye and make it right.

The plan was to aggressively treat the infection with antifungal eye drops and oral medications to bring down the swelling, at which point they would remove the sutures and assess the eye. But after several weeks on that treatment regimen, Freeman was still in tremendous pain. On June 19, she called Dr. AlShaker in the middle of the night. As a fellow, she is already a fully licensed ophthalmologist who spent a further two years gaining subspecialty expertise and is integral in providing acute 24-hour corneal emergency care with Dr. Chan’s supervision. Freeman asked Dr. AlShaker if she should come to the emergency department, because she was ready for someone to remove her eye just to make the pain end.

Freeman made it through that night, but her UHN team booked her in for surgery the following morning. Because the conjunctival tissue was still sewn over her cornea, acting like a patch, Drs. Chan and AlShaker had to dissect it off, using a microscope and microsurgical instruments to remove the sutures and cut away the inflamed tissue so they could see what was underneath. “Her cornea was basically eaten away by the infection and had a hole in it,” Dr. Chan explains. “After exploring what remained of her infected cornea, we proceeded with a cornea transplant.”

Working as a team

According to Dr. AlShaker, the goal of a cornea transplant is to restore the anatomy of the eye and remove the infection by cutting away whatever infected tissue is present and replacing it with new tissue. The cornea tissue essentially works as a cap, protecting the iris, lens and intraocular structures from anything outside the eye. The cornea also prevents the inside contents of the eye from being pushed out during a sneeze or a spike in blood pressure. The time between removing the old tissue and replacing it with the new is extremely stressful because an eight-millimetre gaping hole exists in the eyeball.

This moment requires more than just a cornea surgeon – it requires an OR nurse who can hand over the correct microsurgical instrument without needing to be asked. Bryan Cisneros, a registered OR nurse in the Sprott Department of Surgery, is one such individual, having moved to a focus on ophthalmology from spine and neurosurgery at the beginning of 2021. “The sutures used in corneal surgery are microscopic. As the OR nurse, I have to make sure the correct instrument is being handed to the surgeon. For example, we check that the needle tip, which is about the size of an eyelash, is loaded correctly into the needle loading instrument with the assistance of a bright overhead light,” he notes, adding that the surgical techniques and instruments are constantly changing, as the team acquires advancements in surgical tools to improve patient outcomes.

During that crucial moment between removing the old tissue and replacing it with the donor tissue, everyone on the team, surgeons, anesthesiologists and nurses, is working to ensure each element of the transplant – whether it’s correctly sizing the donor tissue, properly loading suture needles or ensuring a consistent blood pressure in the patient – goes smoothly. “It’s not a one-person show,” says Dr. AlShaker, adding that the anesthesiologists are equally important. Ophthalmology, which works in coordination with anesthesia, is “a very multidisciplinary team,” Cisneros says. “We collaborate to make sure we’re preparing the patient for the best surgical outcomes.”

Freeman’s cornea transplant was successful, allowing her to keep her eye without the infection returning. The healing process takes upwards of 18 months, and her vision won’t improve until the final sutures are removed at the end of that period. Even then, she may need glasses, contact lenses or laser corrective surgery. Still, this is a major win for her. “I’m no longer in pain and I’m not sensitive to light anymore, which is big,” she notes. “And the swelling and redness in my eye is mostly gone, so I look close to normal again.”

– Source: The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2020600,000

Number of people who go blind due to a fungal infection worldwide, annually.

This article originally appeared in the 2023 issue of the Sprott Department of Surgery magazine. Read it here.