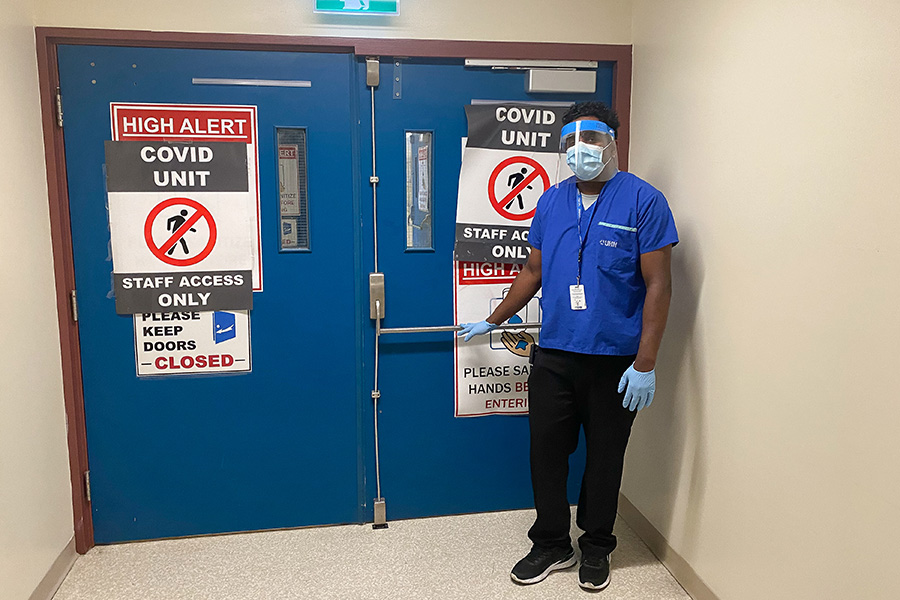

Jeyanthan Markandu, a hospital assistant at Toronto Western Hospital, says seeing the devastating consequences of COVID-19 firsthand makes him laser focused when it comes to Infection Prevention and Control protocols. (Photo: UHN)

Before clocking in to start his afternoon shift at Toronto Western Hospital (TWH), Jeyanthan Markandu makes a stop in the basement.

There, he unlocks a small room and ensures all is in place if he needs to respond to a medical emergency: a bed with a fitted sheet, blanket, full oxygen tank, extra personal protective equipment (PPE).

Jeyanthan then grabs his own face shield, puts it on upside down, out of his face, and grabs two pagers.

As the hospital assistant (more commonly known as porter) working 3:30 p.m. to 11:15 p.m., he carries his own pager – to answer calls to take specimens to the lab, or move patients and equipment around the hospital – as well as the Code Blue pager, for medical emergencies/cardiac arrest. If the Code Blue pager beeps, Jeyanthan is responsible for bringing the equipment in that basement room – within three minutes of the call – and assisting clinical staff at the scene.

“Even break time, if there’s a Code Blue – I have to go,” he says, adding that his last Code Blue was about a month ago, when a patient had a medical emergency in the TWH Atrium. Jeyanthan arrived on scene, waited for clinical staff to assess the situation, helped get the patient on the stretcher and transported them to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

Jeyanthan is one of about 160 hospital assistants who porter patients, specimens, medical gas tanks, blood products and other patient-related items across UHN. They’re part of the Facilities Management-Planning, Redevelopment & Operations (FM-PRO) Department and an integral part of the hospital’s frontline.

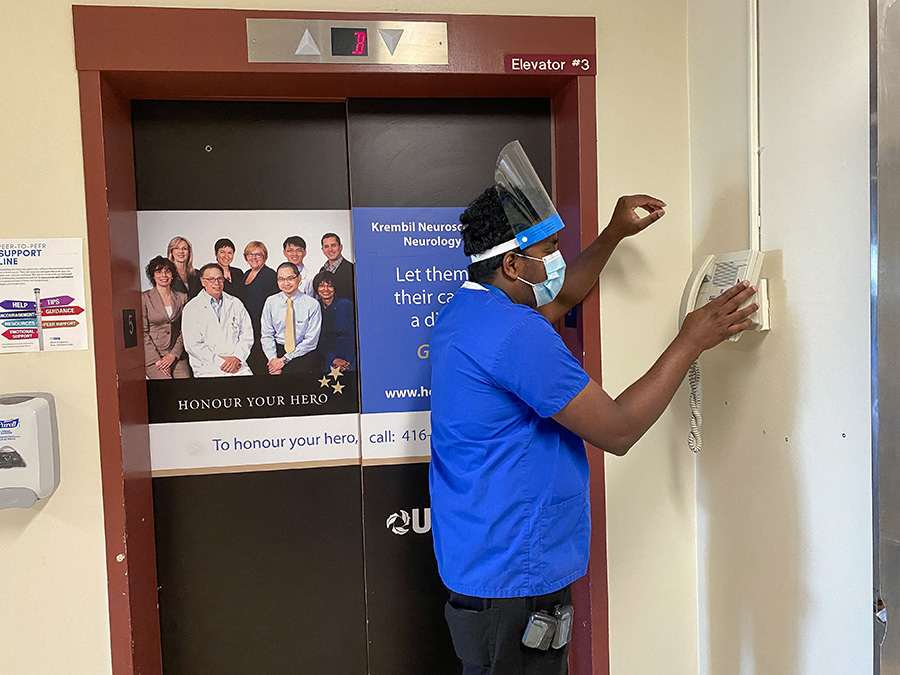

Fifteen minutes into his shift, Jeyanthan’s pager lights up and he heads to the nearest phone.

Hospital assistants receive their assignments through pagers and use landlines to call in to the system for details, accept and clear their calls once completed. It’s a dated system that’s been in place for 30 years. Fortunately, it will be upgraded with the roll out of Synapse, UHN’s clinical transformation initiative, in 2022, moving all hospital assistants to smart phones. Until then, Jeyanthan will make countless trips to landlines – by the elevator, outside a unit – throughout his eight-hour shift.

Jeyanthan accepts his first calls of the day and is on the move. He navigates the hospital quickly, but calmly. He’s hard to keep up with as he takes every corner with ease and seems to intuitively know which elevator will open first.

It’s mainly specimen calls to start. He sanitizes as he gets off the elevator, puts on one glove and grabs blood or urine samples with the gloved hand from a bin at the nursing station. To save himself another call to that floor, he checks for specimens in the unit across the hall before heading to the Central Lab (one of many trips he’ll make there). He hands off the specimen, carefully removes and disposes of his glove and sanitizes.

Throughout the pandemic, Jeyanthan has transported patients from the fourth floor COVID-19 ward all over the hospital – including to the morgue. He’s seen the devastating effects of the virus firsthand, so he’s laser focused when it comes to Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) protocols.

“I’m kind of scared, but I’m just following all the procedures: wearing a face shield, isolation gown, washing hands, so I just protect myself,” he says.

Fellow hospital assistant, Monika Gunness, who he runs into at the Central Lab, recalls how much her job changed when the pandemic started in March 2020.

“I’d never seen this before COVID hit,” she said, pointing to her face shield. “During the beginning, a lot of people were so scared to go in the rooms. We didn’t know what to expect.

“It wasn’t easy mentally.”

Now, more than a year later, the fear has subsided.

“We’re all so confident,” she adds. “I’ve been wearing PPE this whole time and I haven’t got COVID.”

For Jeyanthan, the precautionary measures continue at home, where he has two kids, aged six and nine, and a wife who works in Environmental Services at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

“I put everything in my bag and then I keep it in the garage for two days, then after that I wash it,” he says.

Now that he’s vaccinated, Jeyanthan feels more comfortable around his family, but still won’t have visitors to his Scarborough home.

“It’s been over one year and no one comes in my house – but what can I do?” he says. “We never know – we are working in a hospital.”

By 5 p.m. – just an hour and a half into Jeyanthan’s shift – his colleagues start to clock out, leaving only five hospital assistants on duty throughout TWH. The pace picks up and will only increase as his colleagues continue to head home throughout the evening and Jeyanthan is the only one on duty before night shift starts at 11 p.m.

He receives two new calls: transport a patient from ultrasound to the Emergency Department (ED) and collect soiled intravenous (IV) poles from all floors. The patient call always comes first.

He finds the patient sitting in a wheelchair, sanitizes, puts on gloves, dons his face shield and checks her Medical Record Number (patient identification).

“Even when we’re busy, we always check, because I don’t want to bring the wrong patient,” he says.

He provides a smooth and comfortable transport, tucking in her blanket, ensuring cords won’t get caught in the wheels and slowly moves toward the elevators, carefully navigating any bumps. He gets her to a bed in the ED, locks the wheelchair and makes sure she can manage before he sets off on his next call.

Jeyanthan visits every floor – including the COVID-19 ward – to collect the IV poles, taking every precaution as he goes.

As he heads to the elevator, IV poles in tow, an announcement comes on overhead: “Attention please…”

Jeyanthan stops in his tracks, tilts his head and listens.

“Code White, Code White…”

Not a Code Blue. He continues.

Jeyanthan receives another call: a patient from 5B needs to be taken to MRI. He stops his current assignment – the patient call always takes precedent.

He checks in at the fifth floor Nursing Station, sanitizes, puts on his gloves and face shield, grabs a stretcher, makes sure it’s equipped with enough oxygen and heads into the patient room.

With the help of a nurse, he moves the patient from her bed to the stretcher.

“You O.K.?” he asks, as he adjusts the bed and covers her with a blanket.

Unable to put a mask on herself, Jeyanthan does it for her.

“It’s good for you,” he tells her, reassuringly.

Masking patients during transport is a new COVID-19 protocol and something Jeyanthan never forgets.

“I don’t want anyone else to get sick,” he says.

As it nears 7 p.m., he gears up for more patient calls, because the ED Patient Porter is going on break.

“I know the routine,” he says.

Like clockwork, he’s called to the ED at 7:10 p.m.

Once he gets there, he sanitizes, puts on gloves, as well as his face shield and a gown for added protection.

More calls come in from the ED as the night progresses and fewer hospital assistants are on shift.

While settling a patient, someone he previously transported is placed in an isolation room and going over his COVID-19 exposure with clinical staff.

Jeyanthan isn’t worried.

“When I go in, I’m thinking all of them have COVID,” he says, demonstrating his confidence in the IPAC protocols. “I know I won’t get sick, because I’m protected.”

Although COVID-19 numbers are on a promising downward trend across the province, the ED tells a different story to Jeyanthan, as on this day in late May the majority of patients are COVID positive or pending.

“Everyone thinks we are getting better now, we can enjoy the summer,” he says. “For me? No. We never know what’s going to happen next month.”

His work puts him at risk, but Jeyanthan wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I really love this job,” he says. “I’m always learning something new and helping people.”