Patients with trigeminal neuralgia, like Joshua Johnston, often suffer excruciating pain. Dr. Mojgan Hodaie, a neurosurgeon and scientist at the Krembil Brain Institute, found a way to help. (Photo: Brie Gallagher)

By Glynis Ratcliffe

It was the dead of winter when 21-year-old Joshua Johnston first experienced a crackling shock of pain across one side of his face. He was walking down a street in Elliot Lake, Ont., when, he says, “I thought I had been shot. It came out of nowhere and dropped me to the ground.” After writhing in pain on the sidewalk for what felt like an eternity, he dragged himself into the emergency room which, thankfully, was across the street. “I genuinely believed I was about to die in that moment,” he says.

Fortunately, it only took a few days to determine the source of his pain: trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic facial neuropathic pain linked to the trigeminal nerve. It’s a rare disease – about 12 in 100,000 people are diagnosed with it each year – and it often goes undiagnosed or gets mistaken for other illnesses.

Over the next 16 years, Johnston tried anticonvulsants and barbiturates to help manage his pain, both of which he reacted poorly to, and had three major surgeries, each of which gave him less than a year’s respite from the constant burning and taser-like jolts in his jaw and cheek. “Everything was deteriorating,” says Johnston, a firefighter who has since become a leading fire scientist after throwing himself into his work as a means of coping with the agony.

The disease is so devastating because this nerve supplies sensation to different areas of the face: the lower jaw, teeth, lips, cheeks, forehead, scalp and eyes. The classic presentation of trigeminal neuralgia is recurring flashes of excruciating pain in some or all of these areas, lasting as long as two minutes. The pain can come from actions as simple as brushing your teeth or smiling, or even a gust of wind. Neuropathic pain, which is caused by damage or injury to the somatosensory system that regulates sensation in the body, is generally hard to treat because, like all pain, it is subjective and not easily quantified or measured.

Thankfully, Dr. Mojgan Hodaie, a neurosurgeon and scientist at the Krembil Brain Institute (KBI) and the Greg Wilkins-Barrick Chair in International Surgery, who is also part of the Sprott Department of Surgery and Surgical Co-Director of the Joey & Toby Tanenbaum Family Gamma Knife Centre at University Health Network, is changing that with her groundbreaking work.

Innovative research

Before Dr. Hodaie began studying this disease, most research centred around understanding the blood vessels that reside close to the trigeminal nerve and often compress it. While they do play a role, Dr. Hodaie has focused on studying the nerve itself, since it is the key player generating the pain.

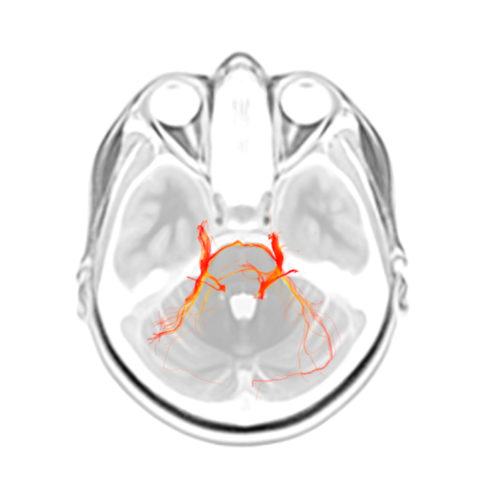

She’s developed and applied novel MRI techniques that allow researchers to zero in on fibres in the brain to investigate both the properties of the trigeminal nerve and the pathway of that nerve in the brain. Dr. Hodaie’s technique mixes anatomical images with colour to highlight the normally black, white and grey fibres. This makes it easier to see which direction they are travelling in. “I use this technique to investigate what’s happening at the level of the trigeminal nerve itself and whether the fibres are altered or abnormal in the setting of trigeminal pain,” explains Dr. Hodaie.

With advanced structural imaging, Dr. Hodaie – who is one of the world’s top experts in this disease and one of the few surgeons in Canada who focus on surgery for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia patients – can develop a better understanding of what pain looks like in the brain. “It’s not just that the nerve changes; there’s actually signatures of pain in key areas of the brain,” says Dr. Hodaie, who has performed well over 1,000 procedures for this disease.

Her goal is to give patients a better understanding of how likely it is they will benefit from surgery, including microvascular decompression or stereotactic radiosurgery using Gamma Knife, which uses focused radiation beams on the trigeminal nerve to treat the pain.

Understanding pain

In 2020, Johnston, who had been experiencing hundreds of shocks a day, was referred to Dr. Hodaie. By then, he was out of options. “I had no hope until I met her,” he says.

She offered him a different approach – neuromodulation using fine electrodes under the skin, which mitigates the nerve’s pain signals through the implantation of a programmable device in the body – and it changed his life. Pain still exists, but he can dial it down to a manageable level with what’s essentially a remote-controlled pacemaker – except the device is pacing his nerves, not his heart.

Dr. Hodaie is now training neurosurgeons at the KBI and around the world, as well as exploring the use of machine learning to study larger and more detailed subsets of brain images. Through this research, she and the team at the KBI will have an even greater capacity to change lives.

They’ve certainly changed Joshua Johnston’s life. Now 37, he can finally carry his four-year-old without worrying about dropping him, and his kids call him “robot daddy” due to his neuromodulator device. “I feel like I woke up out of a coma,” he says. “There are so many aspects of my life that I never realized had been compromised by the pain.”